Flash finding: How drug money from sick people really works

A rose by any other name

It wasn’t all that long ago that those of us at 46brooklyn began referring to prescription drug rebates as “money from sick people.” The reason we selected this particular nomenclature – and we spend a lot of time around here on word choice – was obvious to us at the time. Drugmaker rebates are nothing more than money collected by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), rebate aggregators, and/or insurers, on prescription drugs taken by sick people, that are intended to be used to lower premiums for all people covered by the plan.

Despite the complexity that rebating inserts into the marketplace, the pursuit of lower premiums seems to be offered as a justification for their existence within our plagued prescription drug supply chain. Said differently, the design and incentives inherent within our system can often pit the business of health against actual health. However, despite our best attempts to make the “money from sick people” lingo stick, it hasn’t quite caught on like that whole red flag thing. But we’re not letting it go, and we think we might finally demonstrate why. Over the last year, during a pandemic of all times, sufficient data has come to light that we think, we hope, might finally be able to change our collective mindset on the true nature of rebates and their impact on the U.S. healthcare system.

So indulge us, if you will, with just a few minutes of your time as we use insulin – Lantus in particular – to show just how unfriendly rebates really are to the consumers who need them, and afterwards you can be the judge on which terminology actually best describes the phrase formerly known as drug rebates 😉.

Assumptions

As with any good analysis, we need to start with some data, and some assumptions. As we alluded to in the intro, and fortunately for us, all of our data for this flash finding is publicly sourced, so feel free to check our work, and thank those who make drug pricing data more available and accessible to the public.

Our first assumption is to establish what the average deductible amount is in the U.S. We need this value, because it establishes how much money a patient will have to pay directly for their healthcare service – in our case the drug Lantus – before they get the benefit of their insurance copayment. Thanks to the Kaiser Family Foundation 2020 Employer Health Benefits Survey, we sourced this at $1,644 annually (which honestly, strikes us as low, but we’re going with it).

Second, we need to know what Lantus costs – what it costs for the package to the health system, and what a patient pays to get that package after they’ve met their deductible. Fortunately, this was recently looked into over at 3 Axis Advisors (Disclosure: Two of the members of 46brookyn’s board make their professional home at 3 Axis Advisors). Using the just-released World Insulin Price Comparison Map, we can see that the typical package cost for a box of Lantus pens is $408 in the U.S., with a typical patient pay obligation of $34.34. The cost of the box of pens reported there is at least in line with our own visualizations at 46brooklyn, assuming Medicaid managed care organizations are reasonable proxies to the commercial market, and also in line with other previous disclosures on price.

Lastly, we need to know what kind of rebates Lantus can generate. Lucky for us again, this information came to light at the start of 2021 via the U.S. Senate Finance Committee’s investigation into insulin costs where it was stated “in 2019, Sanofi offered OptumRx rebates up to 79.75% for Lantus for preferred formulary placement on their client’s commercial formulary.” Sanofi is the manufacturer of Lantus, and if the offer of rebates two years ago was 79.75% to one of the largest PBMs, it seems reasonable to assume those rebates are still available today. And in fact, based on what we know about the general growth of rebates over time and recent reporting on Lantus’ net price, we would believe that number to be a conservative estimate for the sake of this analysis. To be clear, the WAC for Lantus hasn’t changed since 2019, and a 79.95% value of the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) equals $339 today (WAC of approximately $425 for a box of pens).

Crunching the Numbers

With those assumptions out of the way, and our data points gathered, we can construct a model that demonstrates how cost for insulin is generally experienced by people with diabetes over the year, as well as the rebates that PBMs, rebate aggregators, and/or health plans are recognizing on each prescription of Lantus. Note, we are grouping PBMs, rebate aggregators, and health plans together in our model because it is largely irrelevant which entity is taking the money, and well, they’re increasingly the same organization.

Once this model is constructed, we can then compare the existing flow of money in regards to Lantus to a different model that recognizes what it’d be like if rebates were instead recognized at the point-of-sale, meaning that the patient would be exposed to the drugmaker’s actual net price. This could be the case today – solutions to put rebates at the point-of-sale reportedly exist – or it could represent what the world might look like if rebates went away. Either way, we’re just presenting the data.

So what does the data show? Let’s find out.

Results

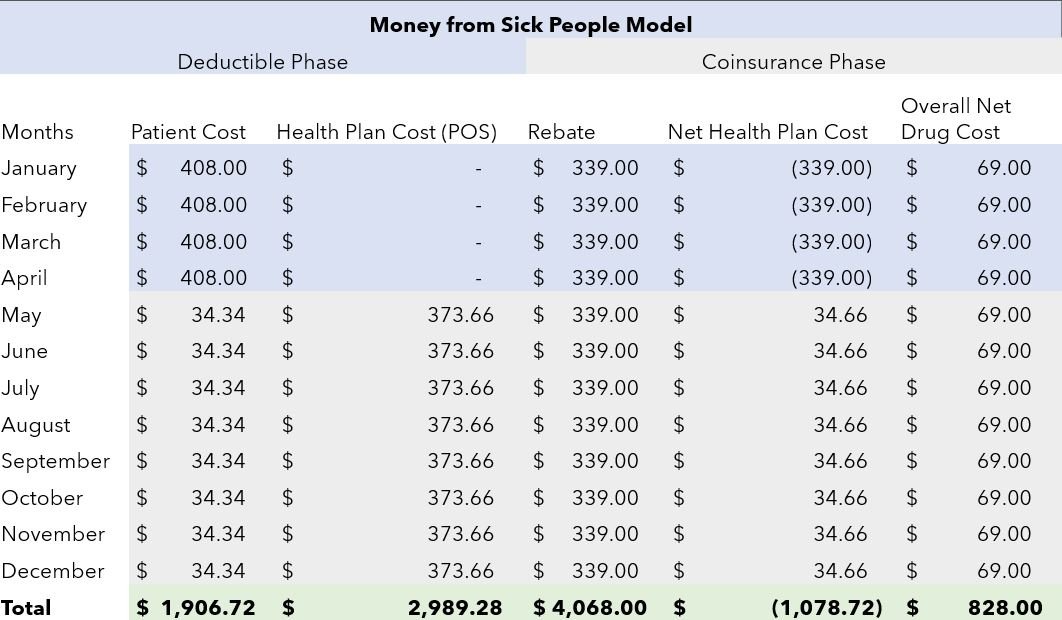

Figure 1 - Money from Sick People Table

Source: 46brooklyn Research

Since Figure 1 is nothing more than a table, it is hopefully fairly straightforward and easy to understand. However, let’s leave no doubt.

In the first column we see how patients are paying for their Lantus over the course of the year.

The second column shows how much the health plan (i.e., insurer/PBM) is paying at the point-of-sale to help the patient to purchase the drug. This amount is nothing while the patient is in the deductible phase, and whatever the difference between what the cost of the product is and the patient copay amount for the remainder of the year.

The third column shows how much rebate dollars are being generated with each fill.

The fourth column shows the health plan’s expenditures in the net (i.e., point-of-sale payment minus rebate collected).

And the final column shows us the actual net price of the drug.

The rows are color-coordinated based upon whether the patient is in the deductible phase or coinsurance phase of their coverage. A quick scan of Figure 1 tells us that during first four months of the year, our hypothetical person taking Lantus is subject to the full ‘list price’ of the product as they accumulate the necessary dollars to meet their deductible. Come May, they’ve accomplished this, and now they start reaping the benefit of having insurance – where they pay a fixed copay amount for their drug, and their insurance is now covering the majority of the cost.

On the surface, this seems like a good deal if we’re only being exposed to the drug’s full “cost” for four months out of the year instead of 12. Behind the scenes, we see regardless of what the patient or health plan is paying, rebate dollars flow. To help contextualize the flow of money over time, Figure 1 is reproduced in Figure 2 as a cumulative bar graph.

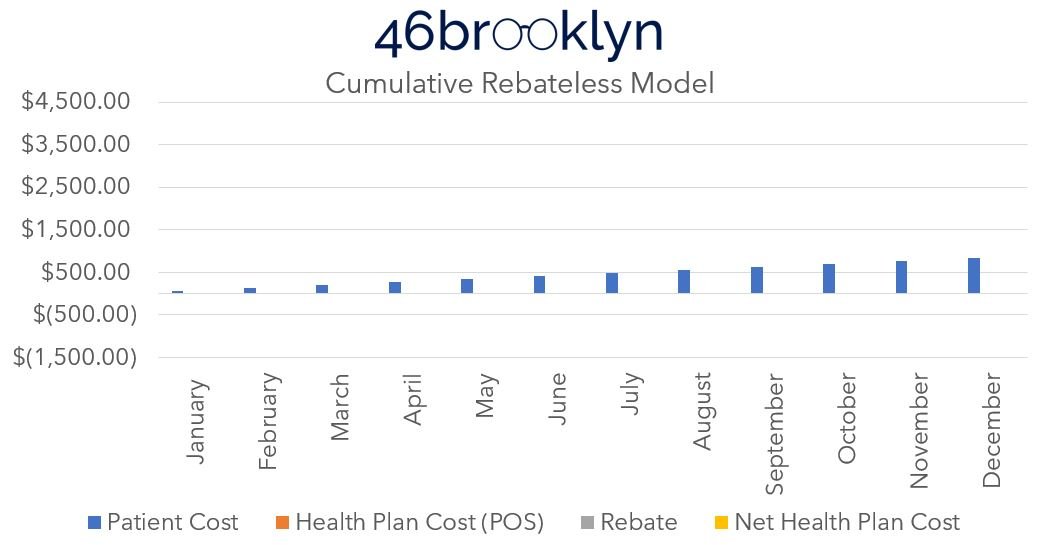

Figure 2 - Money from Sick People Cumulative Bar Graph

Source: 46brooklyn Research

Contrast the figures above with what would happen if rebates were simply point-of-sale price concessions (below). Rather than constantly moving money between parties, the net drug price, which is $69 above (i.e., $408 Lantus cost at the pharmacy minus the $339 rebate), is recognized at the pharmacy counter, and no rebates are collected at any point along the way. For completeness sake, we’ll present both the table and the cumulative bar graph for this second model (Figures 3 & 4 below).

Figure 3 - Rebateless Table

Source: 46brooklyn Research

Figure 4 - Rebateless Cumulative Bar Graph

Source: 46brooklyn Research

What our models show us is that patients are over-paying for vital prescription drugs. In the current “Money from Sick People” environment, a patient expends $1,906.72 annually per year on Lantus alone (absent any premiums they have to pay, and without consideration for diabetic supplies they’ll need to use Lantus properly). The health plan’s total net expenses are -$1.078.72. That is to say, the health plan made around a thousand dollars off the sick patient’s drugs. They did this by collecting and banking rebates during the first four months of the year, and then using those rebates – plus the rest of the rebates that they generate over the remainder of the year – to pay for the expenses to the pharmacy to acquire and dispense the drug (and it just so happens that they have some money left over at the end).

The health plan would likely fire back at our claim that they are making this much money off the rebate scheme, and instead insist that they pass through the preponderance of these rebates to their clients (i.e., employers). While we certainly could quibble over the degree with which drugmaker price concessions are passed through to plan sponsors, this doesn’t change the fact that the patient is overpaying – one way or another, the patient is subsidizing someone – either a large health care conglomerate or their very own employer. In other words, one of these two parties (likely both) are making money off of them. And let’s be clear – as our Lantus example shows, there is plenty of money to go around here.

Regardless of who benefits from this scheme, contrast this experience to the rebateless model. In the first model above, the patient reaches their deductible after just four months of filling Lantus, because they’re exposed to that high list price we’re always hearing about in relation to prescription drugs. However, if the net cost was realized directly by the patient, it would take the patient 19 months (or beyond a year) to pay down the deductible. This of course means that the patient never reaches the full deductible amount in the rebateless model, because they run out of time in the year to do so (because… surprise – Lantus is actually a much more affordable drug when you look at its net price).

And while you might immediately think that would be a windfall for the health plan and/or employer, as they now go the entire year without having to pay any value on the claim, that is actually not the case. Rather, the insurer/PBM/employer loses out on the ~$1,000 in rebate-driven revenue per Lantus-using patient per year, because they don’t get that money from sick people at the start of the year (during the deductible phase when they’re paying nothing).

Money from Sick People

On a recently released episode of the State of Health podcast, one of our board members at 46brooklyn (cough Antonio) discussed an important shift in how pharmacy benefits and overall health insurance coverage works, which was, and we’re paraphrasing a bit here, “We don’t have drug insurance in this country anymore. What we have is managed care.” Taking that a step farther, what we have is a system whose incentives are designed to take the provisions of providing care and manage to make it very, very lucrative to do so. Health plan/PBM conglomerates are Fortune 15 companies, and despite that growth in their "value,” they aren’t necessarily making us any less sick, which again, shouldn’t come as a surprise when we look at their economic incentives.

To be clear, we are overlooking a lot of the warped incentives in this flash finding. Those include, but are not limited to, the following:

how the requirements of Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) calculations also incentivizee high-list prices for healthcare services, including drugs. A fixed 15% margin off a higher cost drug (i.e., approximately $400 Lantus) is more revenue opportunity than a lower cost drug (i.e., approximately $150 Semglee; a Lantus interchangeable product);

the challenges of recognizing point-of-sale rebates given that pharmacies still have to acquire drugs at high-list prices (i.e., you cannot pay a pharmacy $69 to acquire Lantus). These challenges are especially prevalent now while there isn’t broad point-of-sale rebates;

there are no guarantees that a rebateless world will give us Lantus for $69 at the pharmacy counter (though it is worthwhile noting Sanofi currently has a coupon card for $99 Lantus for those without insurance, pretty close to our $69 here). As already stated, pharmacies have to be able to buy it at that price, meaning manufacturers and wholesalers must sell it close to that price in order to to get it to patients;

there are some of us already on low or no deductible health plans with a very generous copay structure. These benefits have been negotiated and fought for via collective bargaining or through the generosity of the company we work for. There are also the poor in Medicaid, which by definition don’t have deductibles. Those folks don’t necessarily know or see the broader brokenness in the market.

Nevertheless, what should be clear by now is why it’s such a difficult sell to policymakers to eliminate rebates. Everyone – from the companies delivering health care services, to those providing insurance, even to some of those paying for your insurance – wins in our high price, high rebate, high deductible system. Everyone except the patient of course. And the higher the list prices, deductibles, and rebates get, the more cash those responsible for delivering health care services can siphon away from the patients they are entrusted to serve.

In our view, we have to get back to the basics of why we even have healthcare in the first place. The point of healthcare is to compassionately serve the patient. If we agree on that – which we assume all will do (at least publicly) – it follows that a system that extorts money from patients without their knowledge has no place in healthcare.

Check out the recent discussion that 46brooklyn CEO Antonio Ciaccia had with Gunnar Esiason on the State of Healthcare podcast, where they discuss the role of PBMs in our dysfunctional drug pricing system.

Last month, 46brooklyn CEO / 3 Axis Advisors president Antonio Ciaccia gave an extensive presentation to the Ohio Joint Medicaid Oversight Committee on how prescription drug costs are being heavily distorted in state Medicaid programs. You can view the presentation here and the slides here.

On that front, Nona Tepper at Modern Healthcare covered the fallout from Ohio, where it was discovered that after the state banned PBM spread pricing in the Medicaid managed care program, PBMs began overpaying pharmacies and clawing back the excess payments months after the claims were initially adjudicated, without netting out the true-ups with the state.

Thanks to Shelby Livingston at Business Insider for chatting with Ciaccia on new start-ups seeking to disrupt the PBM marketplace.

Additional thanks to Erin Brodwin at STAT News for featuring our perspectives on Amazon’s position and progress making their way into the pharmacy marketplace.

Last month, Ciaccia also joined National Consumers League executive director Sally Greenberg in a PBM discussion with Michael Monks on the Cincinnati Edition show on Cincinnati NPR affiliate WXVU.

Lastly, tune in November 17 as Antonio Ciaccia joins panel discussions at the House Committee on Oversight and Reform Republican forum and The Hill’s Future of Healthcare Summit.