How PBMs distort and undermine specialty drug pricing guarantees

A rose by another name

Welcome to another edition of our ongoing attempts to demystify drug prices in the United States. For our long-term readers, it’ll be nothing new to hear us complain about the lack of appropriate context to drug prices despite a dozen different benchmarks that can be relied upon to derive the price of a medicine. Which of course means: If there is more than one price of a prescription drug, then there is no such thing as the price of a prescription drug.

However, we have a special treat today, as we’re pivoting away from a focus on the litany of drug pricing benchmarks, and we are focusing on the follow-on impacts of drug pricing ambiguity. In so doing, we hope to try and re-explain the conundrum of drug affordability and how complexity and opacity can be the enemy of patients and plan sponsors. So same song, different dance.

Specifically, in this report we will demonstrate just how irrational our drug pricing paradigm has become by diving into something that would seem to be simple and straightforward on its surface: definitions.

You see, when we say things like “context is everything when it comes to drug pricing,” what we’re really driving at is the idea that regardless of what a manufacturer may charge for their medication (based upon their list [i.e., WAC or AWP] or net price) or regardless of what a provider seeks for reimbursement for a medication (their usual and customary [U&C]), the price that ultimately matters to most of us is our price (i.e., the amount that we pay to obtain the medication).

That price (and the price our health plan incurs for the drug) is determined by contracts – contracts between the pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) and the health plan, and the health plan and us as patients (which tells us the benefit design we can expect to get with our premium dollars).

Some of the most basic tenants of any contract are the definitions that underlie the terms and conditions. This is also true with healthcare contracts, which typically begin with a section of definitions. Definitions are designed to explain industry jargon in layman’s terms so that if the parties bound by the contract ultimately come to a disagreement over what the contract is doing, someone who knows next to nothing about drug prices or the healthcare industry could help sort it all out (think of a judge or arbiter, who at times will be the ones determining whether or not contractual violations occur).

To the surprise of hopefully no one, there can be pages and pages of definitions in pharmaceutical contracts, given the high complexity of the US drug distribution system. Generally, the definitions are laid out in alphabetical order, so we can almost guarantee that very early on in the contract, there is something that defines what is meant by Average Wholesale Price (AWP). This is because not many other industries have concepts like AWP, and so it needs defined.

As a quick reminder, as it’ll be important later, AWP is a drug pricing benchmark that we have spent considerable time researching and discussing in the past, most notably here and here. AWP needs a definition because it powers, in some way shape or form, nearly all pharmacy transactions, and thus, someone unfamiliar with industry jargon needs to know what is meant by AWP within other sections of the contract. Again, a good contract will link all the terms together in a universal way to avoid ambiguity. As a result, along with the definition of AWP, somewhere down the line in these contracts will be one or more definitions that seek to define the terms “brand” and “generic” and “specialty” medications. Why? Well, we’re ultimately trying to buy these drugs, and our prices will be guaranteed based upon what classification of drug we’re buying (again, unlike most industries where we’re buying a defined product, not a group of product types).

Now, we ourselves are guilty of occasionally using loose language around these terms and therein lies the contextual problem we seek to explore in today’s 46brooklyn drug pricing report. Let us explain.

Background

For the unfamiliar, a PBM contract generally has something akin to the following sections (as we can observe from this redacted public PBM contract with Arkansas Tech University):

Definitions

General provisions

Duties to be performed

Payment terms - Retail, Mail and Specialty drug prices by drug category (i.e., brand, generic, etc.)

PBM services - Formulary, Rebates

Indemnification

Legal

Confidentiality

Exclusivity

Term and termination

Appendices / exhibits

You see, purchasing drugs via insurance does not work like a lot of other transactions we may be familiar with. When you go shopping for groceries, you see the price tag on the shelf and buy the product in relation to that price. You may have a store membership or coupon that reduces the price, but you’re still paying in relationship to that price on the shelf. Whether you buy the name-brand “Frosted Flakes” or the store-brand “Flakes of Frosted Corn,” the price you or others pay at that store is going to be effectively the same in most circumstances.

However, when we try to use the example of buying cereal as a parallel to drug purchases, our analogy quickly breaks down. First, we as consumers don’t have to review dozens to hundreds of pages of a pharmacy benefits contract to shop at the pharmacy, but our health plan does. Second, as we’ve often discussed here at 46brooklyn, there are dozens of pricing benchmarks which could be selected to be a drug pricing benchmark (i.e., AWP, WAC, NADAC, ASP, AMP, MAC, U&C, etc.) and so the price on the shelf doesn’t cleanly equivocate to our shelf price at the grocery store.

For both patients and plan sponsors, the way pharmacy prices work today would be as if, in the future, all shelf prices at the grocery store were digital and changed based on who walked up to the shelf to look (terrifying if you think about it).

In fact, perhaps the only thing our grocery store example gives us of value in relation to a conversation on drug prices is the concept of what a “brand” and “generic” actually are. We know brand-name cereals and appreciate their differences from store brands. Name brand cereals, like name brand drugs, have trademarked names and marketing associated with them, whereas the store-brand (i.e., generics) do not. However, we know that the box of store brand cereal (i.e., generic) is going to give us effectively the same good as what our brand name cereal gives us. And it is upon that fundamental understanding that we use as table-setting for today’s report that demonstrates how the loose contractual definitions that ultimately govern our exposure to prescription drug costs can end up breaking the bank.

What’s really in a name?

Many industry observers believe that there must be universally accepted definitions for “brand” and “generic” medications, but it turns out that is not true. You see, drugs don’t come to market approved as “brand” or “generic” drugs. That isn’t how our regulations in the US are set up. We (through the Food and Drug Administration [FDA]) approve drugs on the basis of applications. That’s right; much like you have to apply for a job, drug manufacturers have to apply to market and sell their products in the US.

The most common of these applications, as it relates to drugs, are New Drug Applications (NDAs), Biologic License Applications (BLAs), and Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs). When the FDA approves drug manufacturer applications along these pathways, they generally confer exclusivity periods to manufacturers in addition to granting approval of the submitted application. Even an ANDA drug may get an exclusivity period (such as the 180 days of exclusivity given to first filers of new “generics” [really, we mean first-time ANDAs]). In addition to the FDA regulatory pathway of licenses and exclusivity periods, the US patent office can grant patents and trademarks to drug manufacturers for the products they develop. To recap, we’re not approving drugs as brand or generics; we’re approving drugs based on the type of application submitted to the FDA, which in turn grants exclusivity for certain periods of times (plus this patent thing on the side).

Why spend this time on background of the drug approval process?

Well, generally, we do have a common understanding of what is intended with industry short-hand for terms like “brand” and “generic.” However, as we have learned time and time again within the world of drug pricing, assuming anything is simple and straightforward is a fast-track to being taken advantage of. And the same is true for our perceptions of what brand and generic drugs are, because our common understanding of those terms do not always align with the contracts that ultimately govern the costs we incur to purchase prescription drugs.

Now before you start wondering why on earth you would follow the 46brooklyn drug pricing nerds down this wonky rabbit hole of drug definitions, trust us when we say that we are digging into one of the most fundamental constructs that can determine the amount we pay for medicines.

We feel it is pretty defensible to say that when someone is referring to a “brand” medication, they’re generally talking about a product approved under a NDA or BLA, that has exclusivity and patents protecting it, and is being marketed under a trademark. This is why you can ask pretty much any pharmacist for the brand name of atorvastatin and get the same answer: Lipitor. This is perhaps also why you can ask pretty much anyone what the brand name is for the cereal with the flakes of corn that are frosted and get “Frosted Flakes.”

Believe it or not, medical training discusses the concepts of brands and generics (most often in the realm of drug substitution laws, bioavailability, and bioequivalence). Similarly, when someone says “generic,” they generally mean a product approved under an ANDA that was designed to be a lower-cost substitution to a historic, exclusive “brand” product (i.e., NDA, BLA). Hence the reverse of our earlier example being true – asking any healthcare expert for the generic of Lipitor and you’ll universally get atorvastatin as the response. To paraphrase Shakespeare, truly, a rose by any other name still works to lower blood cholesterol.

This delineation between NDA and BLA products as “brands” and ANDAs as “generics” has generally been our approach when doing analytical work at 46brooklyn. Our drug pricing visualizations that break costs out between brands and generics do so on a FDA-license basis, where BLA and NDA products are classified as brands and the rest are classified as generics. Despite its usefulness for short-hand, we think it’s safe to say that this methodology wouldn’t necessarily be considered to be perfect to many in the drug supply chain.

To demonstrate, consider the method for assigning brands and generics within our favorite pricing benchmark, national average drug acquisition cost (NADAC). Even our beloved NADAC does not conform to this simple FDA-license definition for brand and generic. We invite you to peruse the NADAC methodology (loyal readers almost certainly have a bedside copy, so us linking to it here is mere formality). What you will find on page 6 is a section outlining “Drug category overrides.” These are the methods used by CMS (and their contractor) to change a product’s designation from brand-to-generic or vice versa. What’s most interesting if you really dive into this section is this is effectively CMS disagreeing with itself. You see, the NADAC brand vs. generic definitions are initially determined based on the most recent “CMS covered outpatient drug product file.” As part of the routine Medicaid duty, we have to determine things like brand and generic status, because Medicaid collects different rebates from manufacturers for their drugs depending on whether the product is a brand or generic. Said differently, CMS already has a reason to assign drugs to “brand” or “generic” style definitions. However, even though CMS already has a system to codify drugs, CMS, for the sake of NADAC, disagrees with the system it has, and so overrides it. Talk about an identify crisis.

Source: Secret behind-the-scenes footage of PBMs determining brand vs. generic classification between business segments

Despite our levity, CMS isn’t alone in its struggle here. Many of the contracts in the system today give immense latitude to intermediaries like PBMs and health insurers to determine what is a brand, generic, or otherwise. To be more specific, we’d wager that the vast majority of contracts in place today have language to the effect that the definition for “brand” or “generic” within the contract says that a special proprietary algorithm determines how a drug will ultimately be categorized.

If that sounds like a squishy way to define something in a contract you may spend millions of dollars on, we’d ask you to consider a hypothetical career in brokering healthcare contracts, as you may be ahead of your field already. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to realize that such ambiguous definitions aren’t really pulling their weight as “definitions.” This is the classic “heads I win, tails you lose” approach to contracting. Giving this kind of flexibility to an intermediary, who presumably is guaranteeing different payment rates based upon brand or generic status, means that the house always wins.

Imagine you’re in a casino, playing the roulette wheel, bet on black, and lo and behold the wheel lands black. You start celebrating until the croupier starts collecting your chips off the table. As you voice your dissatisfaction, he’s unfazed (clearly he deals with this all the time) and simply points to a sign you’d previously overlooked, that says “Casino reserves the right to determine what spectrum of light is defined as red or black.” Sure, the sign may have been in front of you the whole time, but you didn’t really understand or appreciate just what it meant until the rubber met the road. Contracts with definitions like these mean that the guarantee math can be constructed to ensure that whatever way makes the most financial sense for them (not you, silly) will determine what is a brand and/or generic.

We aren’t the first to diagnose this dilemma. One of the esteemed members of the drug pricing Jedi Order, Linda Cahn has a great 2010 piece recently re-archived over at Managed Care Magazine entitled “When is a brand a generic? In a PBM contract.”

As Cahn so eloquently put it:

“PBMs’ freedom under nearly all existing contracts to misclassify drugs – and to classify drugs differently for different purposes – potentially affects virtually every aspect of drug coverage, making contract terms, and the reporting about the satisfaction of contract terms, of little, if any, value to clients.”

And if you don’t believe Cahn or us, well, we have the data to demonstrate the impact of this definitional ambiguity.

You see, while we have had the concepts of brands and generics in the marketplace for decades now (since at least the early 1980s with the passage of Hatch-Waxman), a more recent development has further segmented our contractual drug pricing definitions into brand, generic, and specialty pricing guarantees.

What are “specialty” medications? Well, it probably won’t surprise you to learn – based on the conversation we just had around brand and generic drug definitions – that there is also no universal agreement on what specialty drugs actually are.

Yep, the drug supply chain just collectively decided to start calling a group of drugs “special” and then commenced in complaining about how much these drugs cost. We can see in this in old reports. The earliest MedPAC reports on Medicare drug spending had no mention of specialty drugs, but now we spend a great deal talking about specialty tiers and drug prices.

In the words of the PBMs themselves, Evernorth / Express Scripts says, “Even though less than 2% of the population uses specialty drugs, those prescriptions account for a staggering 51% of total pharmacy spending.” According to their footnote, Evernorth is basing this on their book of business in 2021. Optum / UnitedHealthcare says specialty drugs are 2% of volume, 53% of total annual pharmacy spending (footnote for them says they’re basing this off IQVIA data, and not their own book). CVS / Aetna says specialty drug spending accounts for 54% of overall drug spending (with no details regarding proportion of utilization that’s specialty). Regardless of who you ask, if you want to know where roughly half of your drug spend dollar goes, you have to be talking about specialty drugs, whatever that means.

Sure, a quick Google search around the keywords “specialty drug definition” will give you results with common themes. However, no one will give you a universally accepted definition despite their immense importance to drug affordability. If we return to our introduction on PBM contracting, what we pay for drugs will be priced and guaranteed in different ways based on our definitions for “brand” and “generic.” Think back to our cereal purchase examples. What would your reaction be to loading up your Instacart with a dozen of boxes of “Frosted Flakes” only to find the store filled the order with a bunch of generic (i.e., store brand) “Flakes of Frosted Corn,” but kept the charge on your receipt the same? Would you accept the higher cost for the product you know cost less? What if we told you that is what happens every day with drug prices, but you just don’t realize it because you don’t see full the receipt?

With that out of the way, the rest of this drug pricing deep-dive tackles the high risks – and high costs – of prescription drug semantics.

What we did

We started this investigation by seeking out publicly-facing specialty drug lists for the three largest PBM/insurer groups, specifically CVS / Aetna, Cigna / Express Scripts, and Optum / UnitedHealthcare (note all lists were downloaded in April 2023). Combined, these three PBMs are estimated to manage more than 80% of all prescription drug claims, providing a good representation of broad marketplace impact.

Quick side note, we are going to call these the specialty drug lists for the Big 3 PBMs, but that may not be a perfect (or universal) short-hand for these groups. For example, if you look at the Cigna / Express Scripts link above, you’ll see it’s talking about Cigna Medicare Advantage plans and their specialty drug list with Accredo (the Express Scripts specialty pharmacy before Express Scripts and Cigna merged and became one giant, vertically integrated behemoth). This means Cigna may have non-Medicare Advantage business where they use a different list, but this was the list we found in the public domain, under their logo, and so it’s being attributed to them. If for whatever reason PBMs like Cigna / Express Scripts use a different specialty drug list in different lines of business, we think that speaks for itself, and gets at the heart of this report. For the other PBMs, we’re using a similar approach to their respective lists even if they may or may not be used for all of their clients, all of the time. As we’re trying to investigate whether there are disparities in how certain medicines may or may not be categorized a “specialty,” downloading these public-facing lists from under their logos seems like a reasonable starting point. We would agree that such an analytical approach borders on the edge of “the sins of the father are the sins of the son” kind of reasoning, but given that the Big 3 PBMs we’re studying today are all vertically integrated health plans, PBMs, pharmacies, and much much more, from a legal sense, they’re all the same individual (so we’re not misconstruing the “sins” in our mind). Again, if they agree on what a specialty drug is or isn’t (which is what we want to know), it shouldn’t matter which list, for which client, we downloaded.

After downloading these specialty drug lists, it was relatively straightforward to convert the listed drug names into National Drug Codes (NDCs) based upon string-matching algorithms. Now, the specialty drug lists of the PBMs and their affiliated specialty pharmacies do not delineate dosage forms or strengths. This creates problems when generating a NDC list off of incomplete strings from these lists. It’s possible that some of what we’re capturing as “special” may not fully align to what PBMs do in practice, but in our experience, PBMs often maximize (or even overstep) the confines of definitions and designations, so we can make a highly educated assumption that there will be very few one-off outliers where a certain dosage form may not be treated as specialty versus another. But since we don’t really have better information to inform our analysis (and at least our methods are the same for each PBM, so we’re as likely to run into dosage and strength issues from one PBM to the next), we believe this limitation is properly controlled, particularly since these lists were all the public-facing representations we could easily find demonstrating how these PBMs are characterizing what is and isn’t a specialty drug. They (PBMs) could publish a NDC-specific list, by client if necessary, and there would be no confusion, but unsurprisingly, they are not doing that. Regardless, for the purposes of this analysis, we are accepting their stated specialty designations “as is," and we’d ask that you read today’s analysis with the same “as is” point of view (as you should do with all that we do at 46brooklyn).

Once we had the specialty drug lists downloaded and converted, we set about trying to figure out whether a universal definition of “specialty drug” could be derived. Logically, our first analysis was to compare how many products, on an NDC-basis, each PBM identifies as special. If we saw no major differences in count, that’d be an early signal that there is universality to which medicines are characterized as specialty drugs.

Of course, that is not what we found.

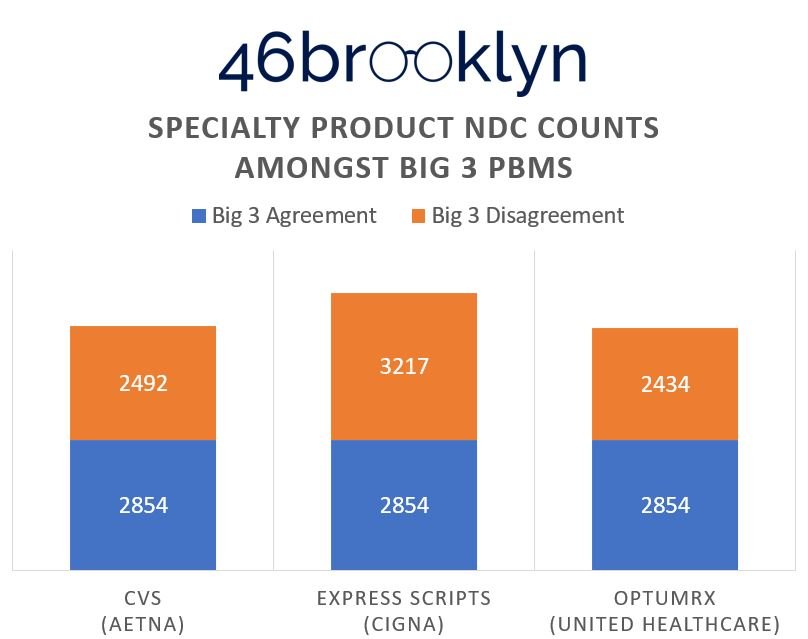

When running our simple count of drugs, we see vast differences between the Big 3 PBM specialty drug lists, which signals that PBMs do not agree (ergo no one agrees) on just what makes a drug special. (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, 46brooklyn Research April 2023 analysis of PBM specialty drug lists (CVS / Aetna, Cigna / Express Scripts, and Optum / UnitedHealthcare)

According to Figure 1, Express Scripts (ESI) has the greatest number of specialty products at 6,071 NDCs, whereas Optum has the lowest at 5,288 NDCs. The Big 3 PBMs agree on specialty characterization of 2,854 NDCs, which ranges anywhere from 47% to 54% of their specialty product portfolio. So, the prevailing market can, all-in-all, agree about half the time what makes something special or not. Considering the fervor over the “excessively high prices and price increases we see each year for specialty drugs,” one would assume that there would be significantly better consistency, at least more so than coin-flip odds, in defining what a specialty drug even is. Said differently (and sarcastically), agreement on “what is” and “what isn’t” a specialty drug aligns with how we decide whether someone “would” or “would not” benefit from surgery – a bunch of people get together and start flipping coins [Sorry Luke, looks like that hand has got to go].

Giving a more specific example of what we mean, take Emgality (galcanezumab), a medication used for migraines. Emgality finds itself on CVS’ specialty list, but not on the lists for Optum or ESI. If this was a reality TV show, we might say better luck next time Emaglity, but the judges have spoken and you’re not America’s next drug pricing idol (don’t worry Lilly, you know you have other drugs gunning for this spot anyway). Alternatively, all three PBMs have Retevmo (selpercatinib), a cancer medication, as special on their list (Congrats Retevmo, you’ve moved passed the judges round and into public voting, lines are now open to cast your vote).

Now, there is almost certainly some role that drug classes play in determining whether a drug is special or not (i.e., all the various forms of cancer requiring individual treatments are more complex than which drug we’re going to use to lower your blood sugar when you have diabetes). We shouldn’t expect the drug development world to stand still, and so maybe there is some reasonableness to adding a “specialty’” designation to historic brand and generic categories (after all, healthcare professionals [doctors, nurses, pharmacists, etc.] seem to have increasing specialization). To the extent that complexity is measured as “special,” maybe we can buy the idea that we’d treat certain cancer drugs as special over other therapies.

However, as we continued to slice and dice the data, we were surprised to discover how many of the products on each specialty drug list within the Big 3 PBMs were ANDA drugs (i.e., generic drugs). Obviously, we’ve done a lot of complaining at 46brooklyn about imatinib and capecitabine prices over the years, but even we were surprised to see what happened to the lists when we broke them out by FDA license types (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, 46brooklyn Research April 2023 analysis of PBM specialty drug lists (CVS / Aetna, Cigna / Express Scripts, and Optum / UnitedHealthcare)

As can be seen above, on an NDC-basis, the most common products within each PBM specialty list were generic (ANDA) drugs.

Unpacking Figure 2, we see that 42% of CVS’ products at an NDC level are ANDAs, 46% of ESI’s products are ANDAs, and 54% of Optum’s products are ANDAs.

Before we unpack that further, let us also orient you to the fourth category in Figure 2, “Not Available.” Turns out, we cannot even agree as to what a “drug” even is.

Recall in our earlier intro, the FDA approves drugs by ANDAs, BLAs, and NDAs, so why are there products on these lists without one of these application types? Well, consider a product like Hyalgan (sodium hyaluronate) on CVS’ and ESI’s specialty drug lists, but not Optum’s. This product is an injection, given by a medical practitioner, into the knee for osteoarthritis. But rather than exert a pharmacological effect, it functions as more of a lubricant. Is that a drug? Depends on your definition of “drug.” And well, CVS and ESI have decided that, for whatever reason, it warrants a position on their special list.

But Hyalgan shouldn’t take it personally. Just because it’s not on Optum’s list doesn’t mean the product doesn’t have restrictions on how it’s used; just that Optum may be managing the product more as a medical benefit than a pharmacy benefit. Why? Well, we can only speculate, but maybe because Optum’s parent company is now the largest employer of physicians in the US, it’s less concerned with site-of-care issues than its competitors, whose doctor office footprint may not be as large. Recognize that ultimately who dispenses the drug is the one who, from a provider standpoint, can make margin off the drug. Pure speculation on our part (and arguably besides the point of today’s report), but maybe CVS and ESI care because they don’t stand as positioned to make money off the provider side as Optum does (at least for now).

Regardless, the key point with the “Not Available” category is to further demonstrate just how important definitions are – for the purposes of their specialty lists, the Big 3 cannot even agree as to which things are or aren’t drugs.

Returning to Figure 2, we should acknowledge that our counting NDCs may be artificially inflating the issue at hand. You see, we were not expecting to find so many ANDA generic products on these specialty drug lists, and now that we’ve found them, we have a counting issue. Are we really trying to count imatinib mesylate 100 mg tablets 28 times because of all the competition amongst generic manufacturers to produce it? I’d wager we are not. So let’s re-do our assessments thus far and count a drug name but once in our measures (Figures 3 & 4 below).

Figure 3

Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, 46brooklyn Research April 2023 analysis of PBM specialty drug lists (CVS / Aetna, Cigna / Express Scripts, and Optum / UnitedHealthcare)

Figure 4

Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, 46brooklyn Research April 2023 analysis of PBM specialty drug lists (CVS / Aetna, Cigna / Express Scripts, and Optum / UnitedHealthcare)

Oh boy. Turns out we may be on to something here.

Sure, it’s no longer that half of all products on PBM lists are special (as we saw before when counting by NDCs in Figure 2), but we’re still talking somewhere between 11% (CVS) and 19% (Optum) of all “specialty” products are generic (ANDAs) when we count by product names (removing duplicate counts of the ANDAs in Figure 4).

Now, we’d be remiss not to pause for a brief moment of sobriety in the face of these numbers:

HOW IN THE FORCE ARE 19% OF THE PRODUCTS WITHIN PBM SPECIALTY LIST GENERIC ANDA DRUGS?

By any reasonable definition, ANDAs are not special. That was the whole point of generics to begin with. That is why we have dozens of versions (i.e., copies) of the same interchangeable products. When you have dozens of something, it’s hardly special.

When the iPhone came out, that was special – who had ever heard of a smart phone before them? But nowadays, an iPhone is one of many, many different types of smart phones. Not all that special any longer. There is only one Jango Fett, but clone troopers are a dime a dozen. When Mevacor (lovastatin, the first statin cholesterol medication) came out, that was special (a brand new way to potentially prevent heart attacks and strokes – i.e., deadly medical conditions). When the 16th generic manufacturer of lovastatin came to market, at that point, it was a tree falling in the woods.

How, even in a galaxy far, far away, could PBMs count so many replicable (and often cheap) generic medicines as specialty drugs?

Knowing what we know now, the next logical question is, “so what?” What might be the impact of these loose designations on the world of drug pricing? We’re glad we think you asked, because we have a new drug pricing visualization dubbed The Super Special Drug Pricing Dashboard built specifically to demonstrate how failing to agree to what is and isn’t special causes financial harm to us all.

Building yet another dashboard to show yet again how distorted US drug prices are

Given that we have these NDC lists of specialty drug products as determined by Big 3 PBMs, now witness the firepower of this fully armed and operational battle station. With an NDC list, and representative payer data on the NDC level, we have all we need to construct a visualization that showcases the problems we face with bogus definitions for everything from “brand” to “generic” to “specialty” to even “drug.”

We already discussed above where we got the NDC list for specialty drugs, but where can we get representative claims data that could help demonstrate a ballpark of the proportionality with which payers purchase specific drugs relative to others?

If you said CMS State Drug Utilization Data (SDUD), then indeed the force is strong with you. As we’ve said before, SDUD gives us NDC-level information on state Medicaid program medication expenditures and utilization, quarter-by-quarter, year-by-year, going back to 1990.

Fortunately for us, we don’t need all that information to demonstrate the impact of definitional maleficence. Rather, we will look at just one year – 2021 – as it is the most current full year data set we have from CMS. Armed with the 2021 data, we first set out to join in quarterly AWP pricing information with the SDUD. This isn’t something we’ve done before at 46brooklyn, so let us quickly explain why.

As we’ve talked about at length in the past (see here and here) and as Ohio drug pricing journalism legends Darrel Rowland and Cathy Candisky helped demonstrate back in 2019, AWP is the underlying rot of the drug pricing system. It is our oldest, but most corrupt, drug pricing benchmark. Lawsuit after lawsuit has demonstrated the unreliability of AWP, and yet, an overwhelming majority of pharmacy benefits contracts (from insurer-to-PBM to PBM-to-pharmacy provider) rely upon AWP to set aggregate pricing guarantees.

So for the purposes of this investigative report, we’re joining in AWP amounts for each NDC, based on a simple average for the AWP prices in the quarter (AWP prices don’t change all that frequently, so there’s low risk of us getting the impact of weighting wrong with a simple weighting approach) to contextualize what the Medicaid programs paid for their drugs in terms of AWP discounts.

Consider a brand medication (we’ll call it Ahsokamine) with an AWP of $100 per prescription. If Medicaid paid $80 for that drug, we’d say within this dashboard that Medicaid paid AWP - 20% for that Ahsokamine (i.e., 80% of the total AWP). Prevailing pharmacy benefits contracts talk about pricing guarantees in terms of AWP discounts or what are also referred to as effective rates. When evaluating drug pricing in this way, it’s important to keep in mind that the worse the discount is, the more money Medicaid paid (So AWP - 20% costs Medicaid more than a claim at AWP - 80%).

After adding in AWP pricing to the underlying Medicaid SDUD and calculating the effective rates, our next step was to join in the Big 3 PBM specialty drug lists. This was straightforward, as the SDUD is on a NDC basis, and our specialty drug lists are also flagged on a NDC basis. With a flag in place, we began assigning drugs to definitions of brand, generic, or specialty in a relatively simplistic way:

If the NDC was on the PBM specialty list, it was flagged as a specialty drug.

If it wasn’t on the list and if the drug was approved under a BLA or NDA, it was defined as brand.

If it wasn’t on the list, and wasn’t approved by a NDA or BLA, we called the drug a generic.

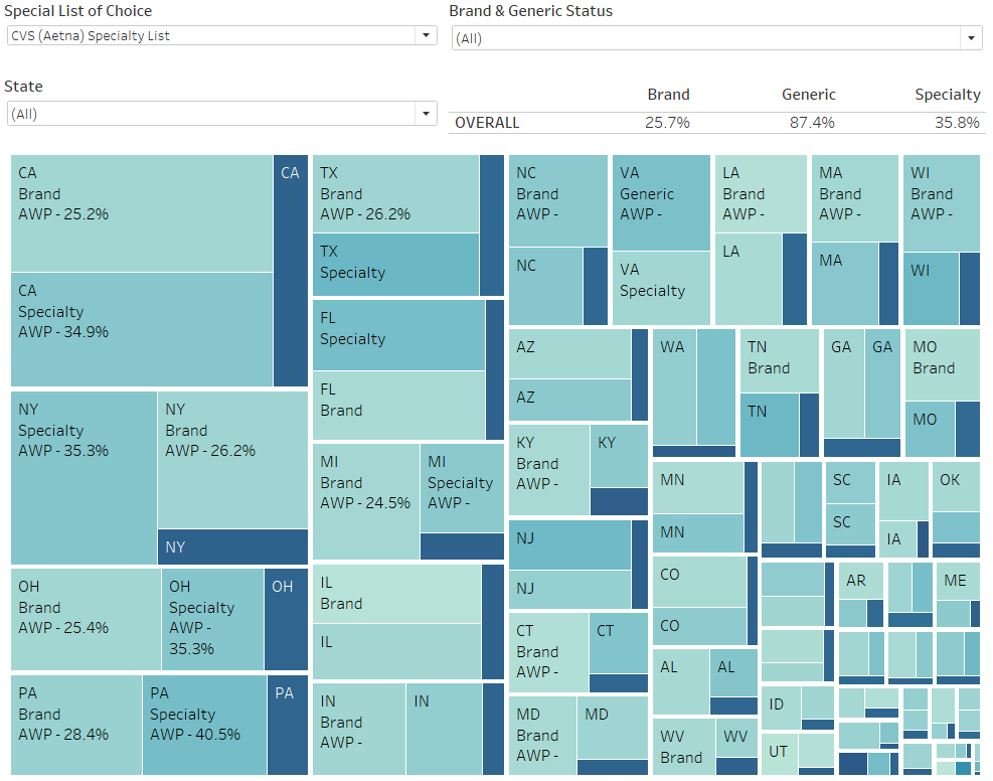

Because the PBMs don’t agree on definitions for “special” (see above), we developed a toggle, which enables the user to switch between their Specialty Drug List of Choice (i.e., CVS, ESI, or Optum). Consider this as a “choose your own adventure” toggle where whichever one you pick will alter your perception of reality, but not necessarily the underlying fundamentals of drug payment.

This last point is the most important to really understand what this new dashboard is designed to show you. What Medicaid actually spent does not change regardless of which reality (i.e., which PBM specialty list) you chose.

Returning to our earlier example of Ahsokamine, if Medicaid spent $80 on the NDC, the AWP is still $100, and the effective rate is still AWP - 20%. However, the toggle may sometimes assign the drug as a brand and other times assign the drug as specialty, depending on our choice of PBM reality. It is the compilation of the various re-shuffles that leads to different perspectives on what drug pricing looks like (but again, not what it actually is, because the price paid doesn’t change).

So with the underlying Medicaid SDUD, we have joined in AWP, and we have flagged each of the Big 3 PBM’s specialty drug lists. From here, we lay out our data into tiles, where each state Medicaid program gets three tiles: brand, generic, and specialty. Each tile is sized based on Medicaid drug expenditures for each state (hence California being in the upper left). We added in a some quality of life toggles to enable drilling into specific states (since some of them get too small to read without hovering over the tiles). We also added a toggle for brand & generic status and a top-line summary bar that keeps us oriented to the overall effective rates of all Medicaid expenditures (so that we can more easily compare individual state results to national trends).

With that background out of the way, let’s take a look at what we assembled – toggled to the CVS specialty list as it’s the first alphabetically (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, 46brooklyn Research April 2023 analysis of PBM specialty drug lists (CVS / Aetna), Data.Medicaid.gov

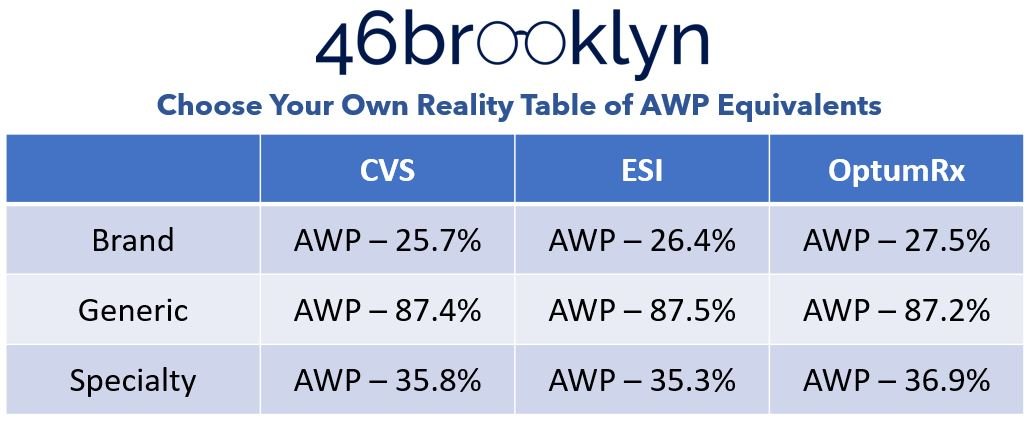

In reviewing our dashboard, as we toggle between the various specialty drug lists, we see the overall Medicaid perception of drug expenditures change based upon which PBM specialty drug list we use. Figure 6 summarizes what happens to the hypothetical AWP guarantees based on how each PBM would theoretically bucket its prescription claims for the entirety of Medicaid.

Figure 6

Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, 46brooklyn Research April 2023 analysis of PBM specialty drug lists (CVS / Aetna, Cigna / Express Scripts, and Optum / UnitedHealthcare), Data.Medicaid.gov

In reviewing Figure 6, if you were shopping for PBM benefits, the choice seems obvious, right? We clearly get the best deal with OptumRx. OptumRx is giving a better AWP discount for both “Brand” and “Specialty” medications compared to its competitors. Sure, we pay slightly more for generics (0.3% in its most extreme [relative to ESI’s generic rate]), but not in a way that seems meaningful given the up to 1.8% greater brand discount and 1.6% greater specialty discount (and the fact that generics are supposed to be cheap). If you’re a payer, you know that brand and specialty medications are what drive your overall expenditures (see above) and so you’ll want to contract with the company that gives you the best discounts on those drugs, right?

Right?

…Right?

Wrong.

Recall that the underlying Medicaid expenditures do not change regardless of which reality we chose. Again, this is fundamental to properly interpreting our new dashboard. The dashboard is based upon 2021 Medicaid drug utilization data. Those claims are long settled and all we’re doing to achieve the differences between the PBMs in Figure 6 is redistributing which buckets prescription drug claims are recognized within based on the lists that show how each PBM subjectively defines which drugs are brand, generic, or specialty. Giving PBMs the power to define what is a specialty drug gives the perception of greater savings where none actually exists.

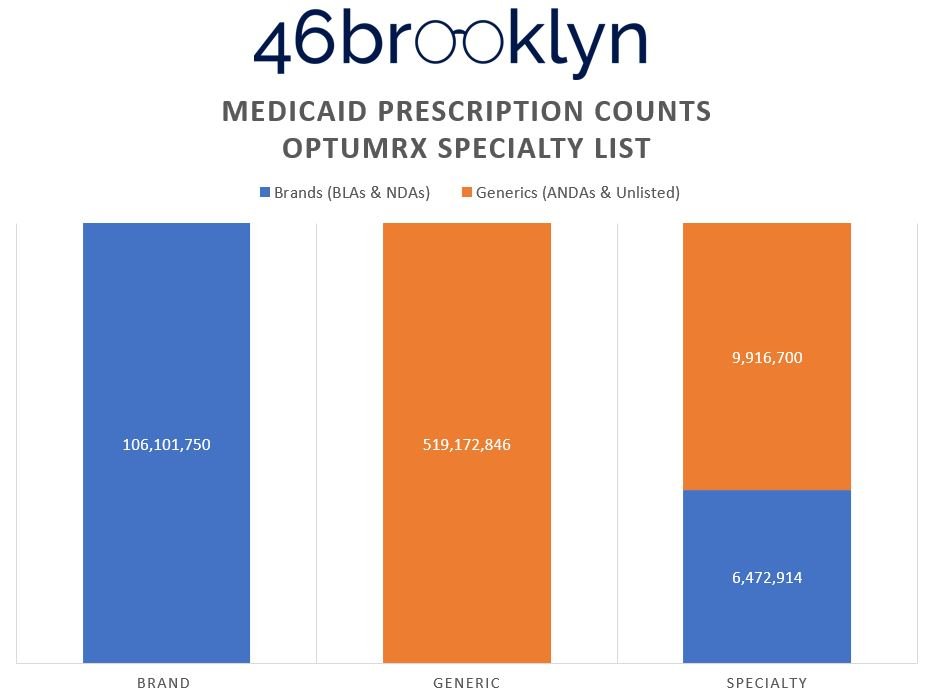

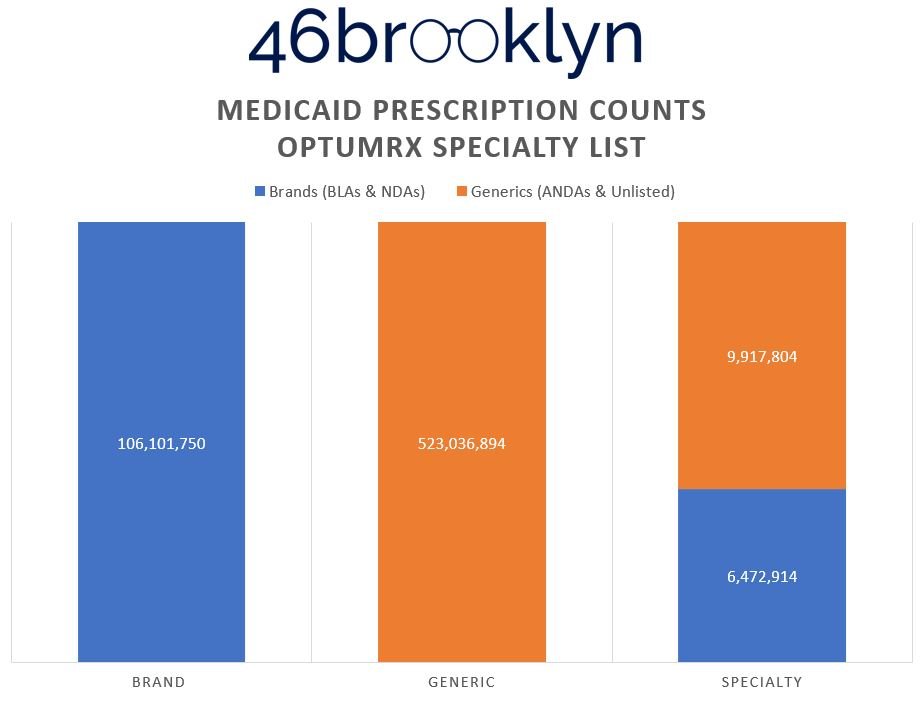

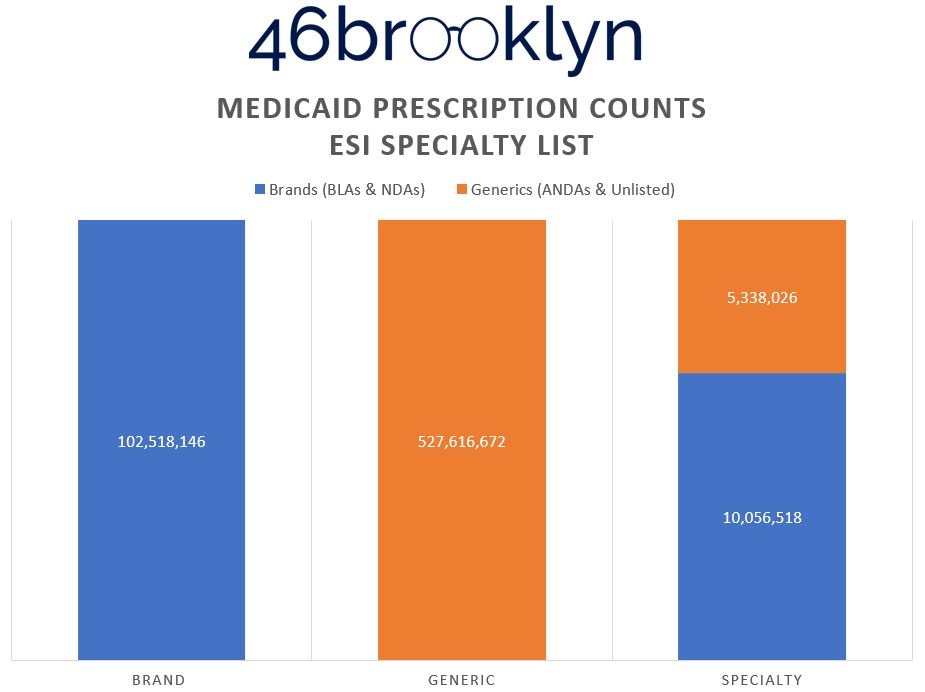

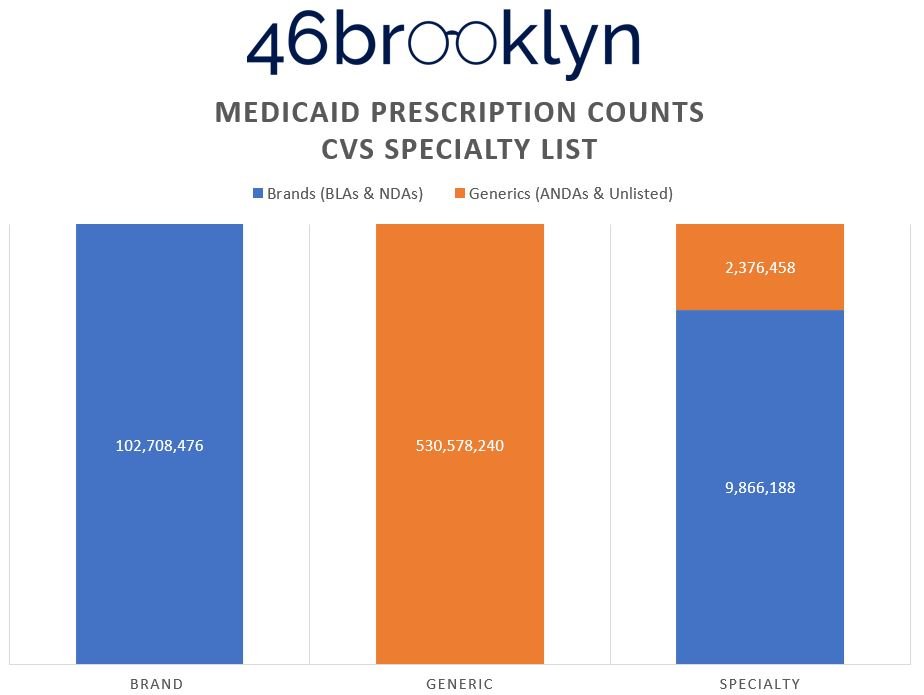

To prove this, Figure 7 (the gallery below) shows the distribution of prescriptions within each of the drug categorization buckets from Figure 6.

What we can see in the Figure 7 gallery above is that in order to present the reality that it yielded, Optum has the lowest generic drug prescription count (almost 7 million fewer compared to CVS), but the highest presence of generic specialty claims (double to triple the numbers of its competitors). Why? Claims that CVS and ESI defined as brand and/or generic drugs have to get reassigned into the specialty category. Maybe this is why some PBMs don’t seem to want to publish their annual drug reports anymore (we might catch on). Creating this new segmentation enables them to distort and optimize the payer experience. Said differently, if you’re a plan sponsor telling the PBM that you’ll choose them based upon their brand and specialty guarantees, so long as the PBM can control the reality of what can be categorized as brand and specialty, they can deliver whatever artificial reality you want.

Back to our good friend Linda Cahn, she refers to these hollow promises as “fish guarantees.” As reporter Marty Schladen distilled the idea, “To explain how PBMs get out of making better deals, Cahn compared PBM contracts to a fish market that advertised all fish at $7.95 per pound. But ‘fish’ in the ads is followed by an asterisk, and in the fine print, it says that the market gets to decide what constitutes ‘fish.’ Not bluefin tuna or Chilean seabass, but tilapia and swai. In other words, you'd be overpaying for what the store called ‘fish’ and locked out of the kinds that would be a good deal at $7.95.”

To drive home this point, we downloaded the list of products available at Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company to analyze just how many the ANDA drugs that the Big 3 PBMs categorize as “special” that are also offered by Cuban. To be clear, we’re looking just at the drugs that are licensed by the FDA via an ANDA. This would mean that the availability of products through Cuban in this analysis is likely understated. But today, we’re not interested in studying the maximum impact of Cuban to the Medicaid program. Instead, all we’re looking for is a way to test how “special” these drugs really are.

If Mark Cuban as a relatively new market entrant, can already dispense these medications, it would again seem to support the argument that there is nothing all that “special” about these drugs. As such, our analysis of ANDA product availability within the overlap between specialty drugs and Cuban’s Cost Plus can serve as a test of our belief that ANDAs are not all that special to begin with (and the purpose of specialty generics is therefore nothing more than to segment the market into ways that make PBMs money).

What we see when we do this analysis using Medicaid drug utilization (in Figure 8 below) is that regardless of which PBM’s artificial specialty reality we pick, Cuban’s shop has you covered on a specialty ANDA basis 66% of the time based on ESI’s worldview of specialty drugs, 71% based on CVS, and to up to 84% on Optum’s.

Figure 8

Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, 46brooklyn Research April 2023 analysis of PBM specialty drug lists (CVS / Aetna, Cigna / Express Scripts, and Optum / UnitedHealthcare), Data.Medicaid.gov, Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company

Now, before the more clever of you go, “but wait 46brooklyn, the generic definition you’re thus far relying upon is intermixing those ‘Not Available’ products (i.e., the Hyalgan’s of the world) that you told us about earlier.” Yes, that’s going to skew the results. Worry not, though the truth we speak doth lack some gentleness; we tested for this, and it doesn’t matter. In Figure 9, we present the Optum data with the “Not Available” products removed. It ends up dropping around 1,000 specialty generic prescriptions and about four million generic drugs. Neither result in a change to the aggregate AWP discounts to either bucket (at least as measured to the tenth decimal place).

Figure 9

Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, 46brooklyn Research April 2023 analysis of PBM specialty drug lists (CVS / Aetna, Cigna / Express Scripts, and Optum / UnitedHealthcare), Data.Medicaid.gov

To appreciate how harmful this whole system can be, let’s look at the ANDA products in particular. It doesn’t matter which reality we choose (i.e., CVS, ESI, Optum), when we toggle the Brand & Generic Status indicator to just look at the generic drugs, we can get a greater appreciation for just how clever PBMs really are. In Figure 10, we’re toggling the Optum Specialty List to just ANDA drugs (they have the most, so the impact will be the greatest).

Figure 10

Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, 46brooklyn Research April 2023 analysis of PBM specialty drug lists (Optum / UnitedHealthcare), Data.Medicaid.gov

What we see is that the overall generic effective rate guarantee being produced based on all state Medicaid program drug utilization is AWP - 87.2%. For Specialty Generics, the guarantee being produced is AWP - 77.9%. By putting in products with an AWP - 77.9% discount into their specialty list, Optum produces a greater specialty discount than its competitors (what we saw earlier); however, given that these are ANDA drugs, it’s in effect robbing Peter to pay Paul.

If these generic drugs were guaranteed like any other generic product (i.e, AWP - 87.2%), expenditures on these drugs would decrease by over $325 million. That is the difference between paying for this select group of generic “specialty” drugs at a worse rate than the going generic rate (i.e., the value of segmentation). Since each 1% AWP in the Generic Specialty segment is worth $35 million, the just over 10% difference between the AWP guarantees is responsible for this potential savings. Three hundred and twenty five million dollars, in one year (give or take a few million), certainly isn’t chump change, but maybe this galaxy of drug pricing distortion is too large. Maybe we’d benefit from a trip down memory lane.

Re-diagnosing the cancerous design of the US drug pricing system

A long, long time ago, in a 46brooklyn report far, far away, we began our drug pricing journey with a story about imatinib mesylate (generic Gleevec). If you’ve been following our story, you know that we like to use imatinib as a poster child of sorts of generic drug pricing dysfunction. And despite five years of constantly banging the drum over this one simple drug, the system is so addicted to it that it still appears on PBM specialty drug lists to this day. In fact, all three of the PBM lists we’re relying upon today still have imatinib listed on their lists as specialty drugs (we’ll save you the clicks and just show you some screen shots in Figure 11 below).

Figure 11

Source: April 2023 analysis of PBM specialty drug lists (CVS / Aetna, Cigna / Express Scripts, and Optum / UnitedHealthcare)

Despite half a decade of being called out for thousands of dollars in markups per claim, PBMs to this day still cannot be bothered to move off this one drug, despite the fact that it has become dirt cheap to acquire.

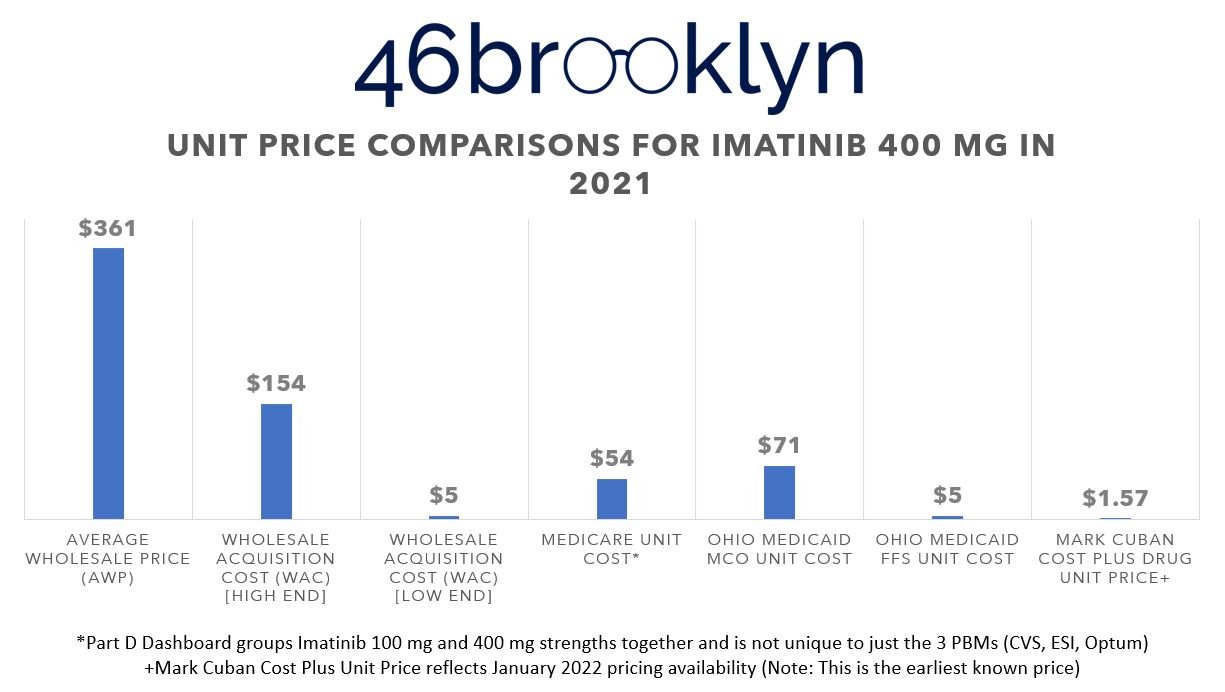

To drive home the point, let’s do some quick price comparisons of these drugs in programs we know these PBMs were operating in back in 2021 (when all the data of this report is based upon). We’re talking about programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

In 2021, all three of the PBMs from our list were vendors with one or more of Ohio’s Medicaid managed care organizations. Specifically, Caresource of Ohio had Express Scripts, UnitedHealthcare had Optum, and the remaining MCOs (i.e., Buckeye, Molina, and Paramount) used CVS Caremark. If you recall from our 2019 report on the Ohio Medicaid PBM saga, PBM spread pricing was prohibited at the time, meaning that the SDUD for Ohio should effectively tell us what pharmacies were collectively paid by these PBMs for each covered medication (unless of course, PBMs are finding new ways to collect spread). Back in 2021, Figure 12 shows the average price of imatinib mesylate 400 mg in Ohio’s Medicaid managed care program (so a weighted representation of the role of each of these PBM’s specialty pharmacy practices), alongside what the state Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) program was paying, what Medicare was on average paying for all imatinib scripts (based upon the Part D dashboard), what the AWP and WAC information ways (thanks to this earlier study), and what the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug pricing was back in January 2022 (again, thanks to this earlier study; Cuban didn’t launch until January 2022 so this is as close of a comparison as we can make).

Figure 12

Source: CMS State Drug Utilization Database (2021), Big 3 PBM Specialty Drug Lists downloaded in April 2023 (CVS / Aetna, Cigna / Express Scripts, and Optum / UnitedHealthcare), Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database (GSDD), CMS Medicare Part D Dashboard

The typical imatinib mesylate 400 mg prescription will be of 30 pills (one unit per day). Therefore, imatinib remains the best (but not only) way of demonstrating how to turn a cheap, $50 drug into a $2,000+ prescription charge. Not to pick on Ohio (after all, they eventually fired the PBMs in question), because it’s truly happening everywhere, but look at them. They know how cheap this product is, look at what they were paying for it in their own FFS program (effectively what the NADAC cost for the drug is). And yet, the largest part of their Medicaid program, the MCOs, were overcharging them. But of course, take another look at what Medicare’s price was – Medicaid MCOs weren’t the only source of drug pricing disparity for this drug relative to its cost. What more could we at 46brooklyn do? We have literally been complaining about this since 2018 and yet the same games persist.

AWP: Always What’s Profitable

In Figure 12, we also see why PBMs still use the hyper-inflated AWP drug pricing benchmark for their contracts as opposed to more modern benchmarks (like WAC, which was defined in the 1970s).We know $2,000 seems expensive, but how does an 80% discount sound (i.e., the difference between AWP and what the Ohio Medicaid MCOs/PBMs charged)? When we joined in AWP data to our dashboard, we also joined in WAC. If you hover over the cells, you’ll see not only the value of 1% of AWP for the prescriptions in that tile, but you’ll also see the value of 1% of the Total WAC. In this case, AWP is 2.5 times more expensive than WAC. This means that the 10% gap would “only” produce $130 million in savings if the same percentage difference was applied to WAC costs (as opposed to AWP).

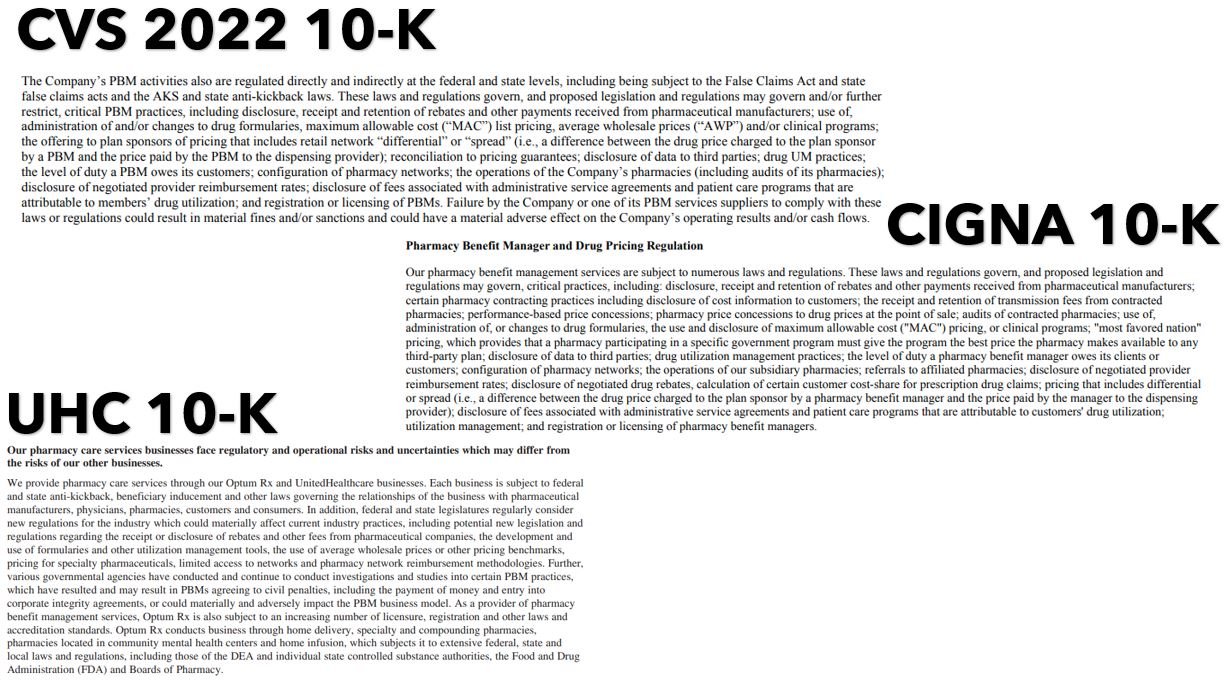

If you question why PBMs continue to cling to AWP, look no further than the financial disclosures of the Big 3 (Figure 13).

To paraphrase what the annual 10-K filings for CVS, ESI, and Optum, are generally telling potential investors, “if we don’t have the ability to price drugs as we wish (AWP discounts, MAC, whatever else), the house of cards goes boom, and our ability to produce profits for you is under threat.” (Note: Nothing in the site constitutes professional and/or financial advice lest you mistake our meaning here).

This is noteworthy, considering that AWP was understood to have been materially impacted and fixed over a decade ago after multiple legal settlements over the inflated and broken nature of AWP. However, the policy fallout of those lawsuits were limited and contained to the brand drug space, which left the drug channel ample real estate to work around and undermine the expected positive outcomes.

As Deloitte pointed out back in 2009, “The two drug pricing publishers will reduce the AWP of thousands of National Drug Codes to a uniform 1.20 of WAC effective Saturday, September 26, 2009. The reduction will apply not only to the 400 brand name drugs involved in the lawsuits, but also to several hundred other drugs that have markups beyond 1.20 of WAC. While this may potentially result in a savings to self-insured plan sponsors and other third-party providers who negotiated the purchase of drugs based on AWP, the PBMs with whom these contracts are drawn are expected to move quickly to adjust contracts to maintain the economic parity that existed prior to the settlement.” (Emphasis ours)

Further, in her March 2009 order and opinion in the seminal AWP case, Judge Patti Saris unleashed Force lightning on the industry, stating, “AWP has been exposed as a faux inflated price unrelated to actual drug prices. Reliance on AWP is a trap for unwary and unsophisticated TPP purchasers and results in consumers paying unwarranted co-payments. Not only do FDB and Medi-Span have the right to make these changes, but in my view, after eight years of this MDL, rolling back AWPs or phasing them out as a pricing benchmark is in the public interest and to the benefit of the class.”

Check the date of that quote again, folks. Here we are more than 14 years later, and AWP continues to be the backbone of prevailing pharmacy benefits contracts, and its use in conjunction with squishy and pliable drug category designations in pharmacy benefits contracts enables the old arbitrage schemes with new, slightly modified logistics.

Back in 2009, after the settlements, Drug Channels’ Adam Fein asked an important question: What happens when AWP goes boom?

Well, the answer is here. And just like the destruction of the first Death Star, the impact of the first boom never destroyed its devastating weaponry.

It’s as if the dark lord of AWP was hurled down a chasm and blown into oblivion. But somehow, he’s returned.

And unfortunately, perhaps its power is more than could have been imagined.

The ability for PBMs to subjectively categorize medicines as brand, generic, or specialty – or which drugs are covered under the pharmacy benefit or medical benefit; or hell, which drugs will even be considered as a drug – provides a galaxy of opportunities for hidden mark-ups and manipulating drug prices.

It should come as no shock that this degree of complexity is not straightforward nor simple. You have to put in a lot of work to build architecture with this many nuances. The simple and efficient thing for a PBM to do would be to base a drug’s price on its actual cost, slap on a transparent fee, and be done. But alas, patients and plan sponsors are stuck navigating a tangled web of jargon and proprietary numbers with not so much as a gaffi stick. (For our non Star Wars nerd friends, what we’re saying is we’re bringing a metal stick to a laser sword fight, and unsurprisingly, we’re losing the duel).

If we had a system where price was known, objective and consistent, these disparate discount equivalencies and drug categorizations – and the consultants and lawyers needed just to understand them – would no longer be needed.

Return to our overall Medicaid effective rate guarantee picture in Figure 5. Medicaid is collectively getting approximately AWP - 25% on brands and AWP - 35% on specialty. Under what logic does it make sense for specialty drugs to achieve a better discount rate than the regular, old brands?

The story that PBMs and health insurers have told us is that specialty drugs are driving our drug expenditures (i.e., around 3% of specialty drugs are responsible for up to 50% of drug spending). If those drugs are so special, how are the PBMs negotiating better discounts on these limited, restrictive, less competitive products compared to the more run-of-the-mill brands?

Well, maybe they’re not. To be blunt, it appears as though the entire concoction of the phrase “specialty” has been used as a means to undermine pricing guarantees and overcharge payers for some generic drugs such that the “special” drugs seem cheaper than they actually are. At the same time, PBMs are giving their clients, plan sponsors and brokers what they’re asking for. For plan sponsors who say they have no interest in getting drug definitions right but only want to buy the contract that gives them the lowest price on their cost drivers (i.e., brand and specialty medications), PBMs are using the latitude of definitional ambiguity to create the artificial reality that wins them the business (regardless of whether their competitor would charge them the same amount of money, just under a different set of circumstances). That is the key learning from today’s dashboard.

Well, isn’t that special?

We began today’s report under the premise of trying to demonstrate the importance of context in understanding drug prices, while trying to ignore what those prices actually are. We believe we demonstrated how Shakespeare got it wrong as it relates to drug definition roses, where one PBM may call a rose (i.e., specialty) what another calls a weed (i.e., a generic). Then we learned how the intersection of definitions and prices enables our misaligned system to continue to function despite increasing scrutiny.

That said (and yes we realize a lot has been said), we but scratched the surface of the issue.

Consider that not once did we mention that most contracts require that PBMs are the sole entity able to dispense a plan sponsor’s specialty drugs or PBM services (see “Exclusivity” section within PBM contracts). So when we saw that plan sponsors were being overcharged on certain generics to make specialty pricing guarantees look more appealing, it probably bares further investigation given that the party best positioned to benefit from the decision to overpay on these specialty generics are the PBMs themselves. The impacts to what we intend to measure through things like Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) or insurance premiums are stories for another day.

The American Academy of Actuaries tells us we have to do something about specialty drug spending. Consultancy group Aon tells us that too. Even Optum hilariously tells us, “Nowhere is the need for actionable insights more acute than for specialty medications.” However you get your information, we’ve been told that we have a big problem with specialty drug costs. And in a general sense, they’re not wrong.

As we showed in our March report on launch prices, the latest, most innovative drugs that are coming to market are often more expensive than the drugs that came to market in the previous year. But our perception of the severity of that issue is clearly clouded by the role of a transaction intermediary (i.e., PBMs).

Is anyone shocked when this year’s Ford F150 is more expensive than last year’s model?

Were we surprised when the latest technology, such as the cost of the first electric cars, were more expensive than the older, internal combustion, technological models?

In general, there is a collective belief that even with the increased prices of these automotive innovations, there is a general improvement with the underlying value of the purchase.

Yet, having a confident debate about the value of new drug therapies is significantly undermined, because there is such little transparency into what drug prices actually are. And as we’ve shown today, our perceptions of price are often undermined by subjective terms and definitions set by intermediaries who profit off complexity and inflated prices.

We’re left asking ourselves a pretty jarring question: What if one of the big problems with specialty drugs is the very fact that we’ve told them they’re special?

There is no question that we have increasing drug affordability challenges. Much of those challenges are most pronounced with brand medicines and those routinely designated as specialty drugs. But when so many drugs considered to be specialty aren’t all that special, it intentionally distorts our perceptions of the value of intermediaries who claim to achieve bigger savings on specialty drugs.