Generic Lyrica launches at 97% discount to brand version

There aren’t many things in this world that rile up patients like prescription drug prices do. Every year, the headlines seem to roll off an assembly line:

“No end in sight to rising drug prices, study finds”

“Drug prices in 2019 are surging, with hikes at 5 times inflation”

“Prescription drug prices are out of control”

While many drug prices are skyrocketing, there are others that are doing quite the opposite. In the aggregate, the net impact is, well, complicated.

But regardless of whether or not overall costs are spiking too high, the U.S. prescription drug patent system is designed in a way to ensure that if a drug is expensive, eventually, the brand manufacturer who brought the drug to market will lose its exclusivity, and generic manufacturers can produce copies of the brand. The increased competition typically drives down the costs of those previously expensive medications.

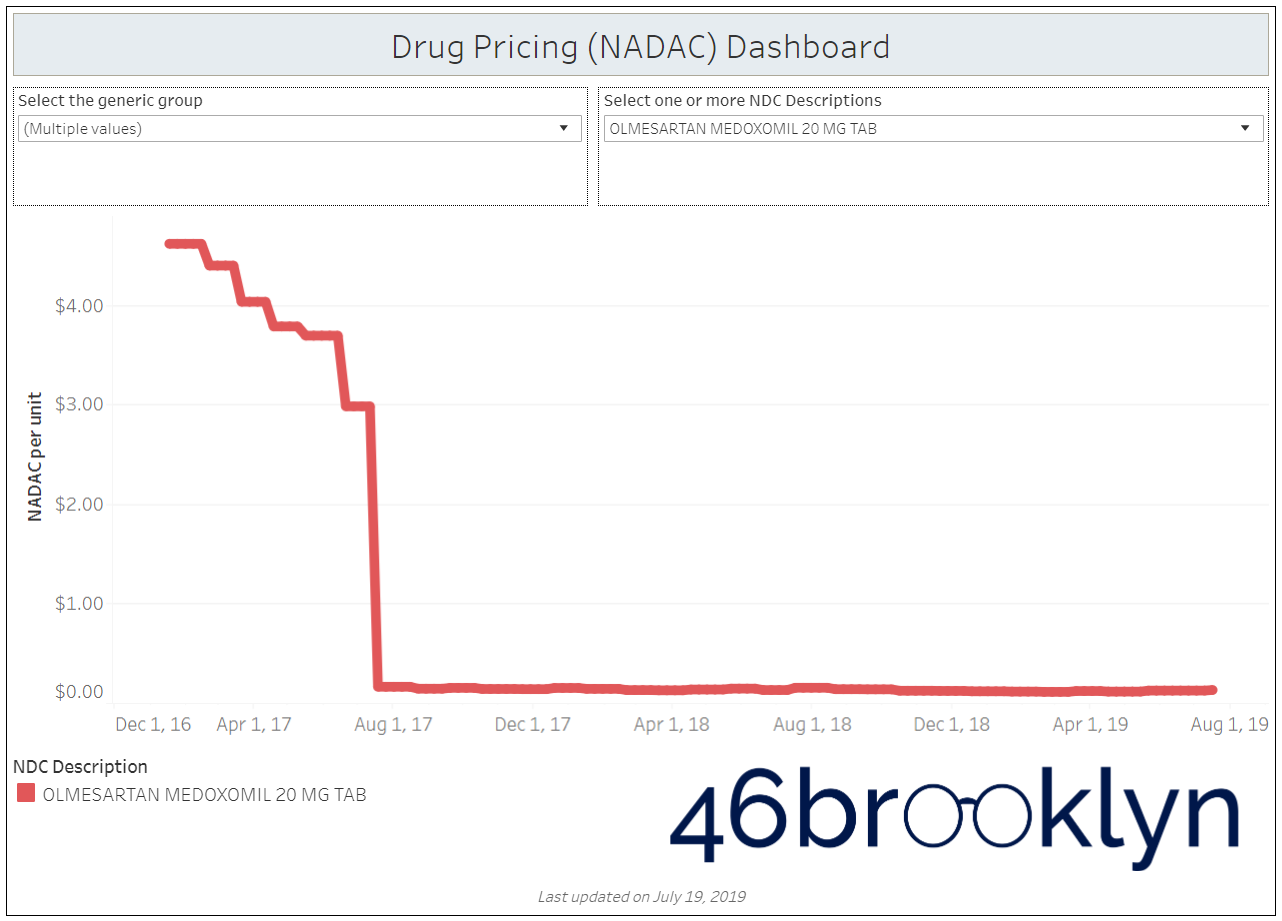

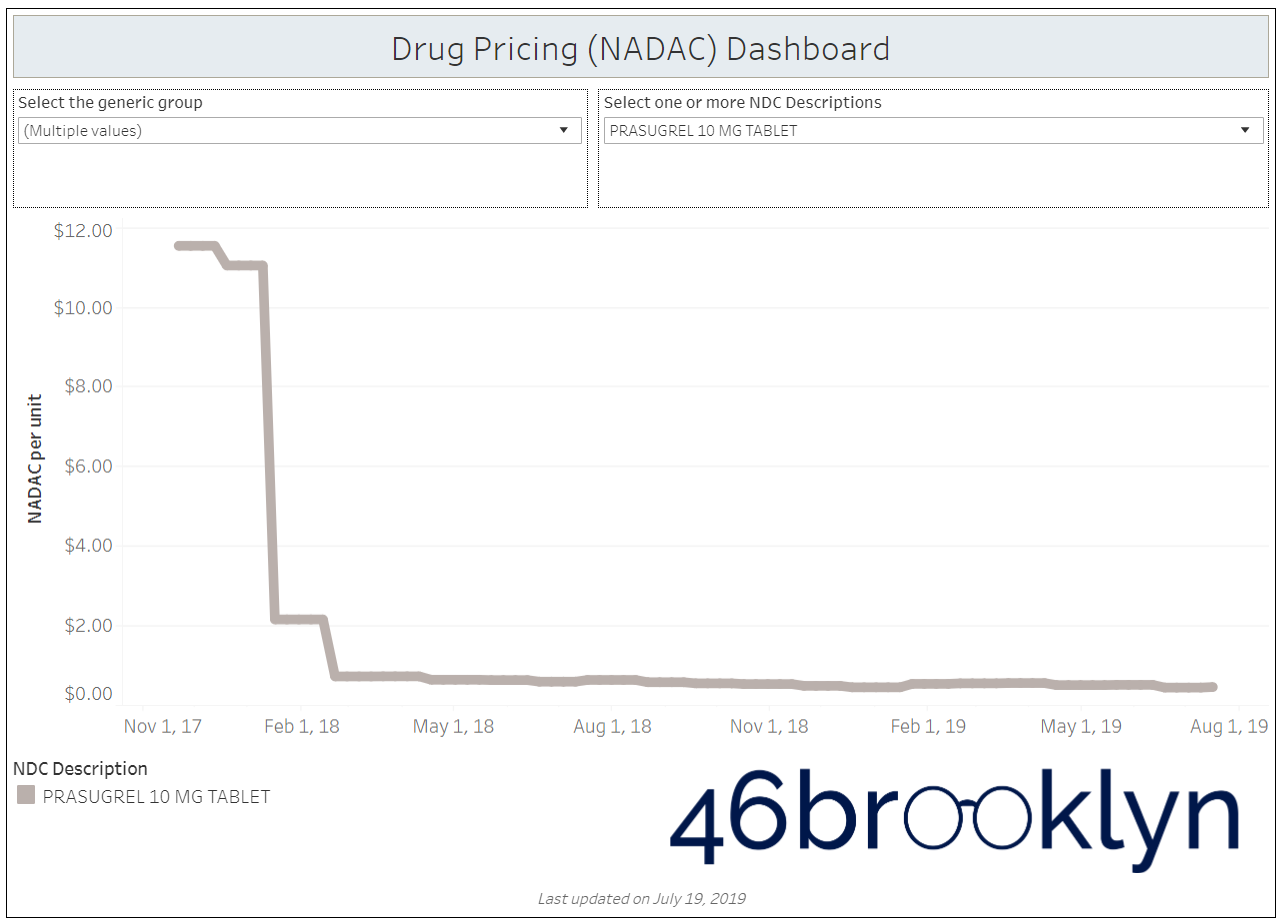

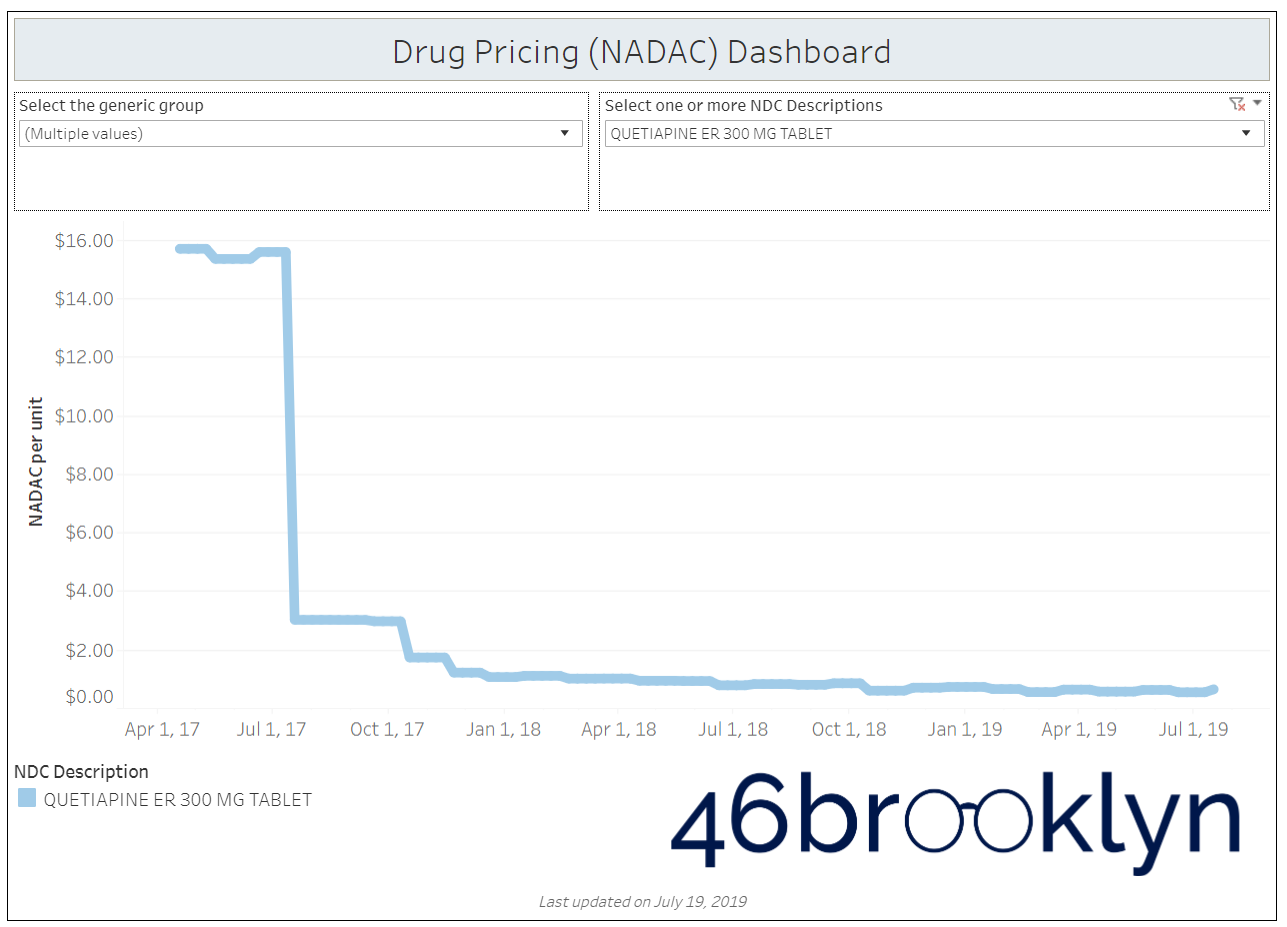

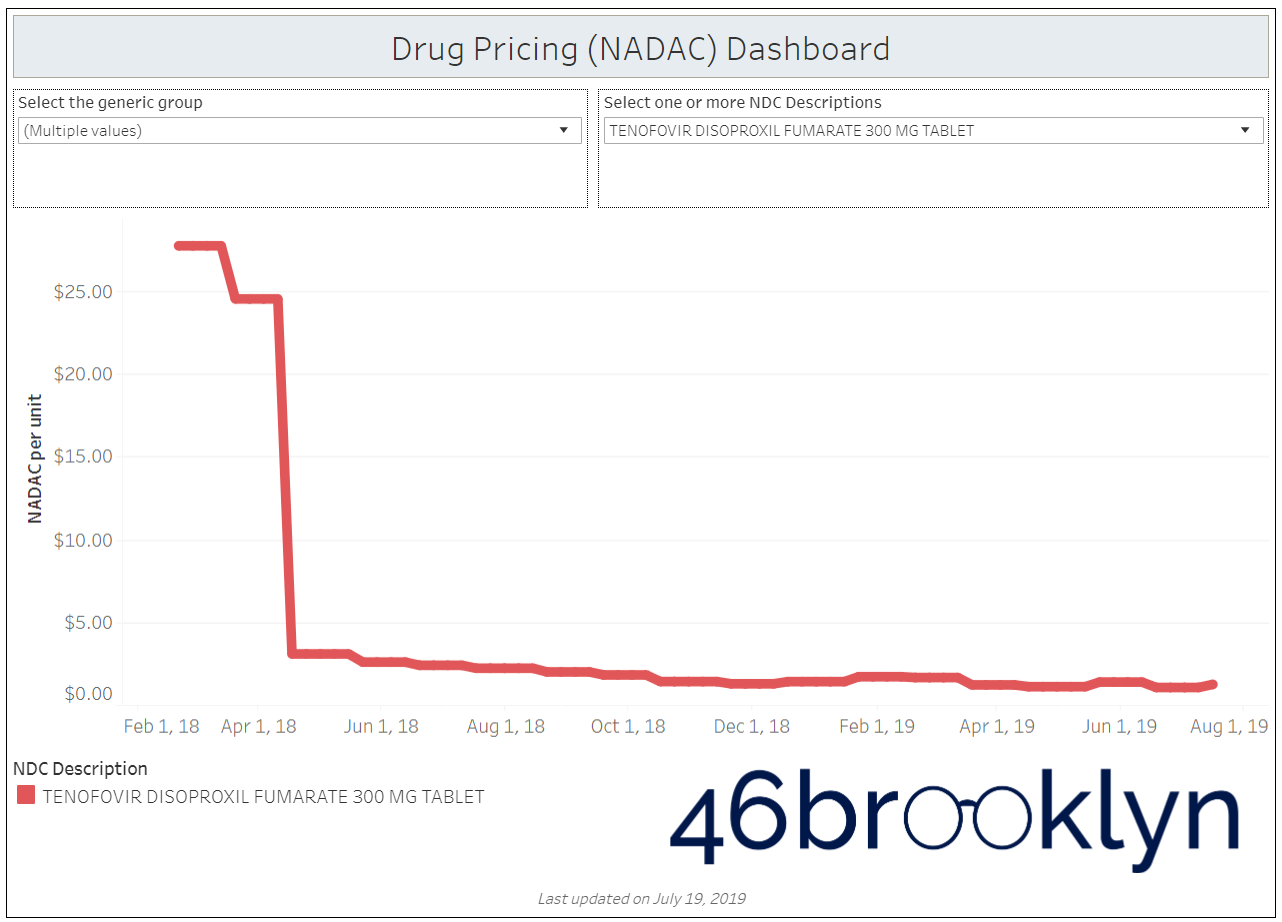

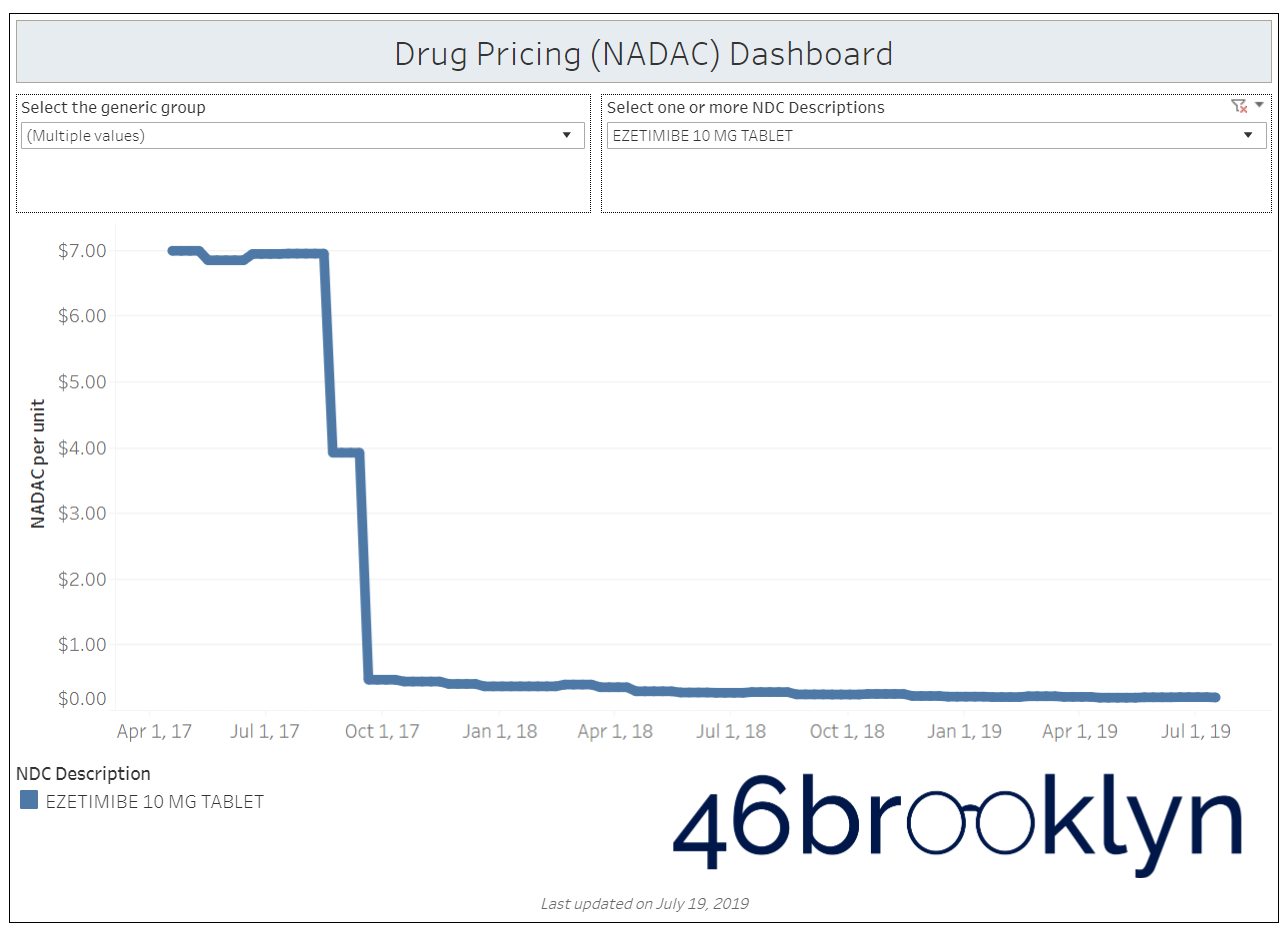

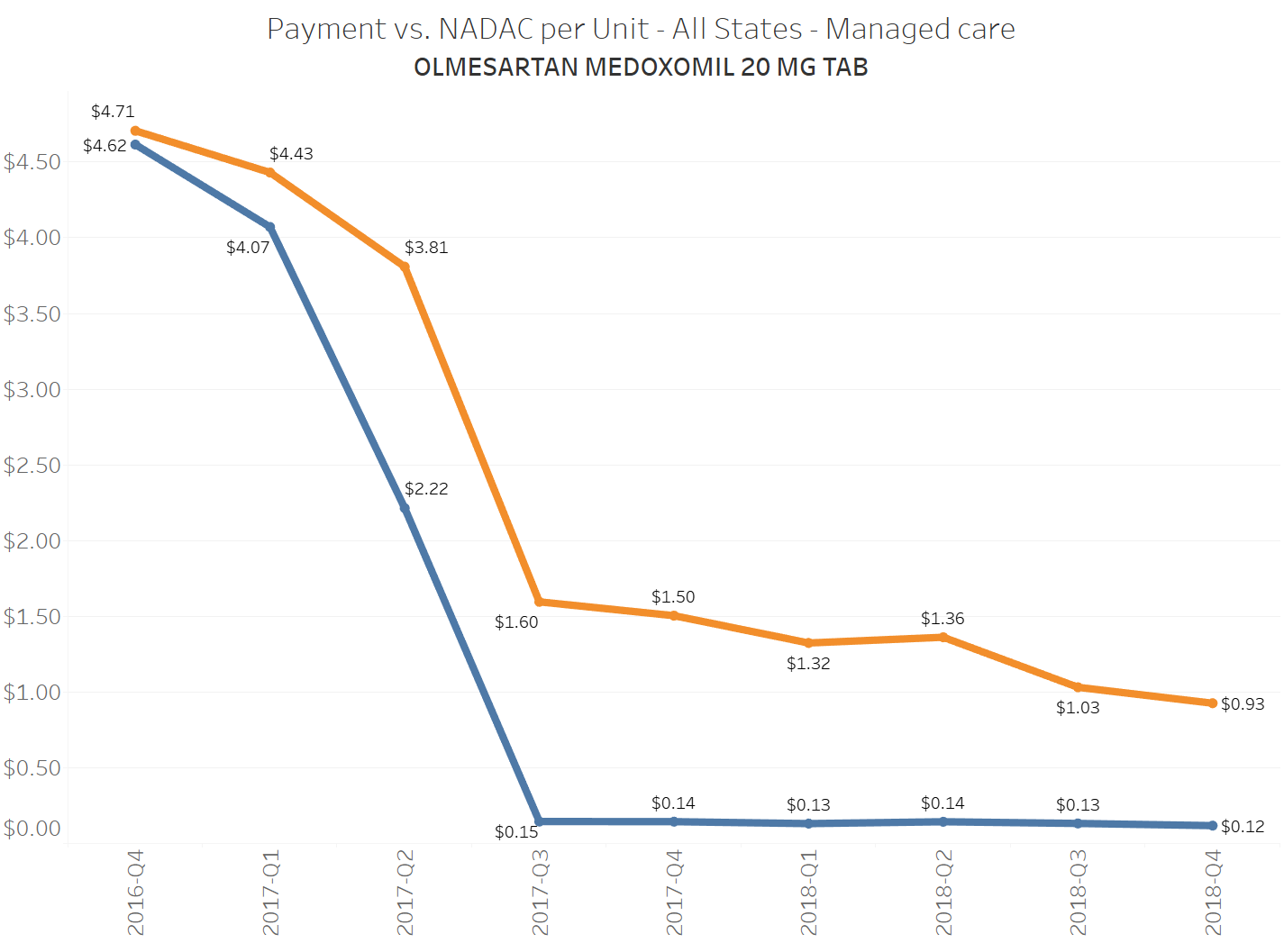

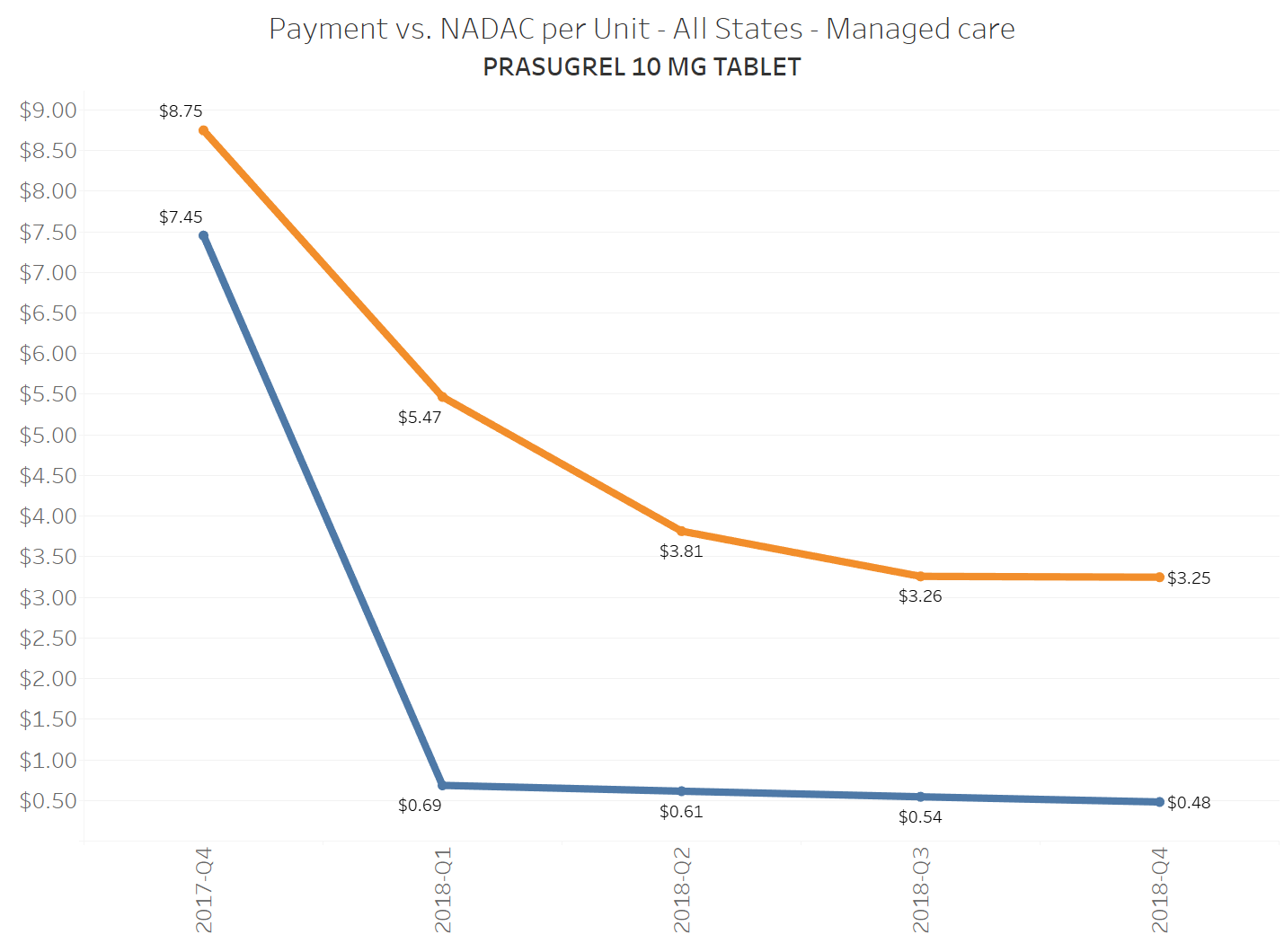

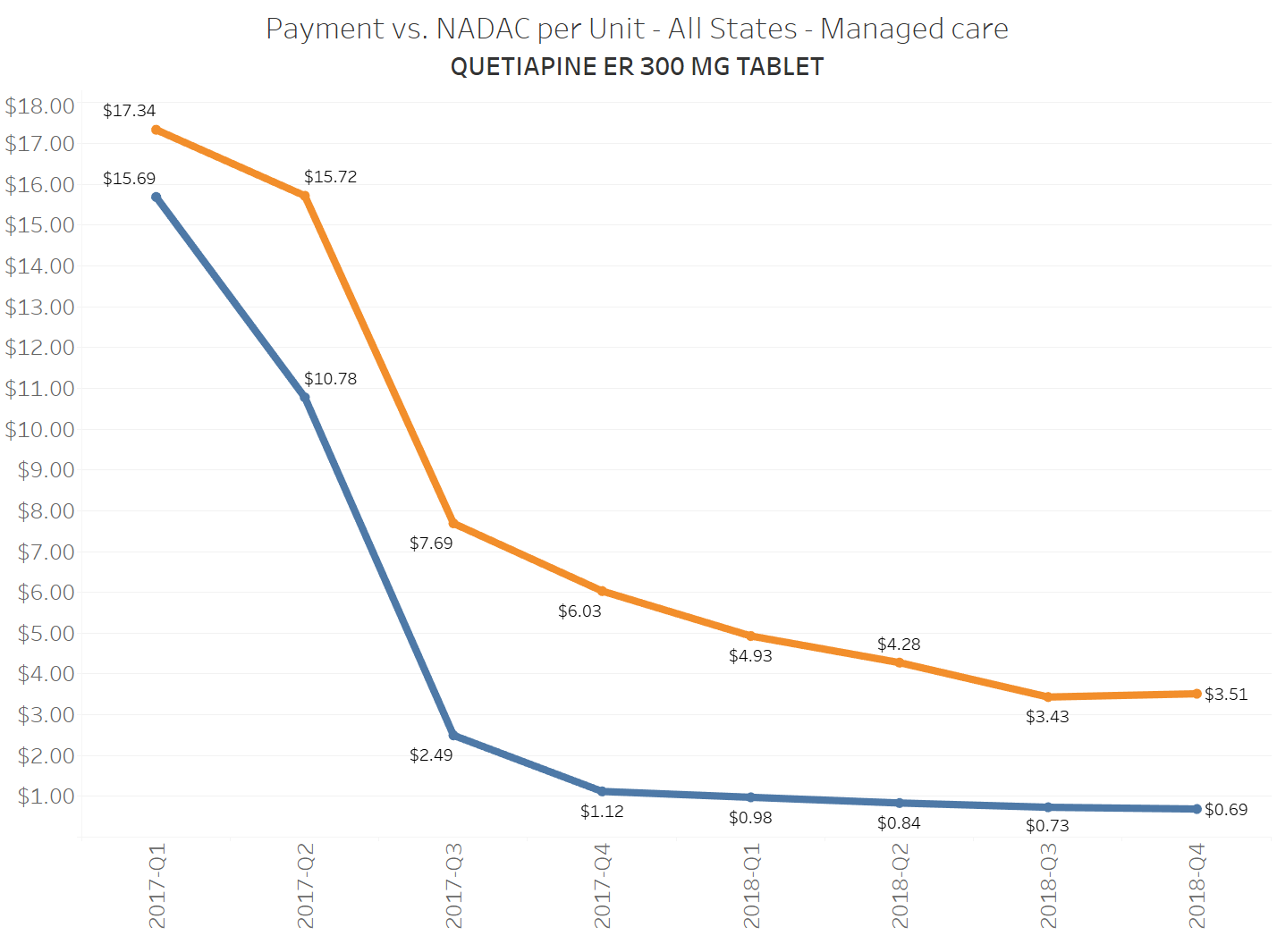

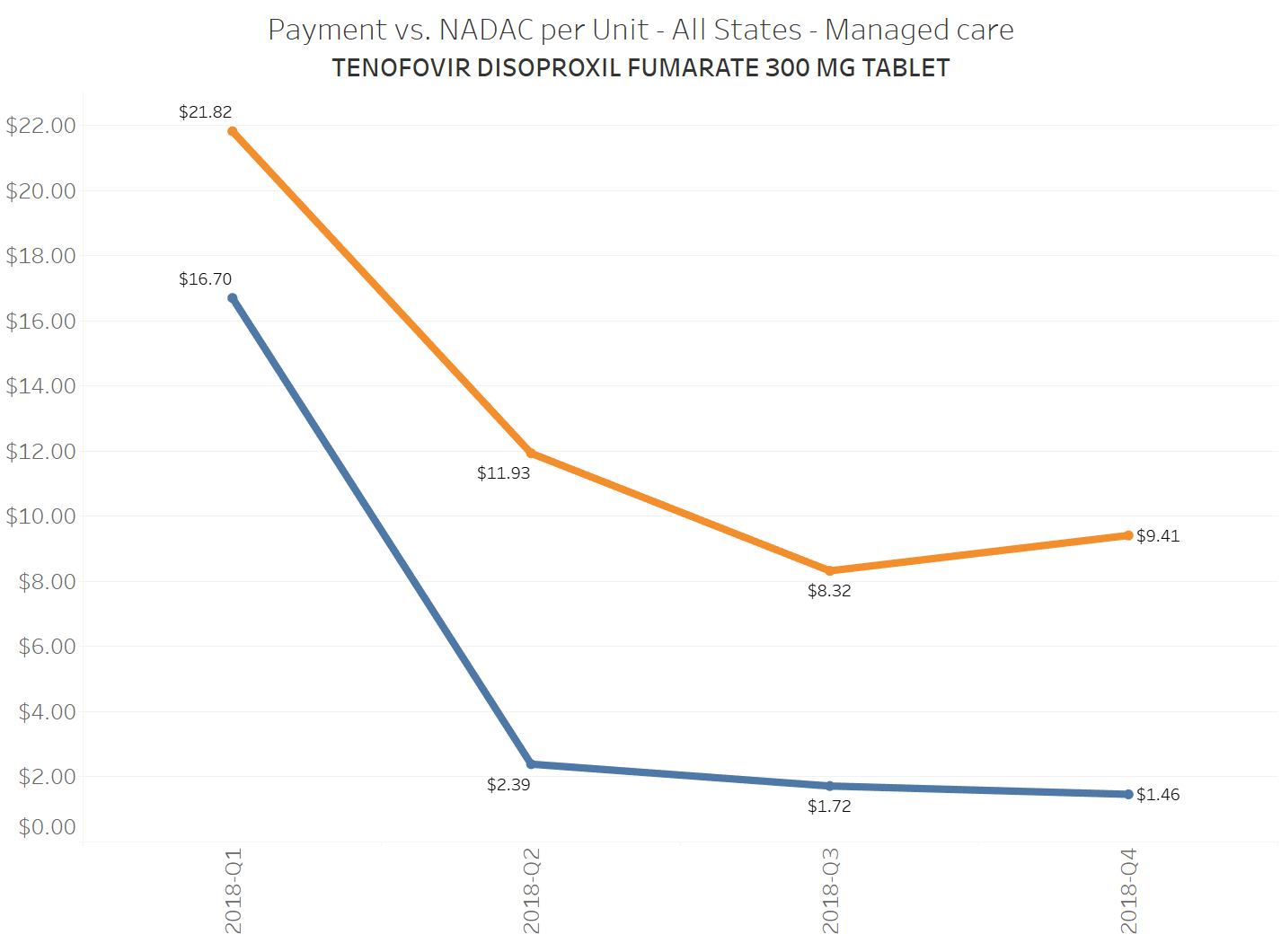

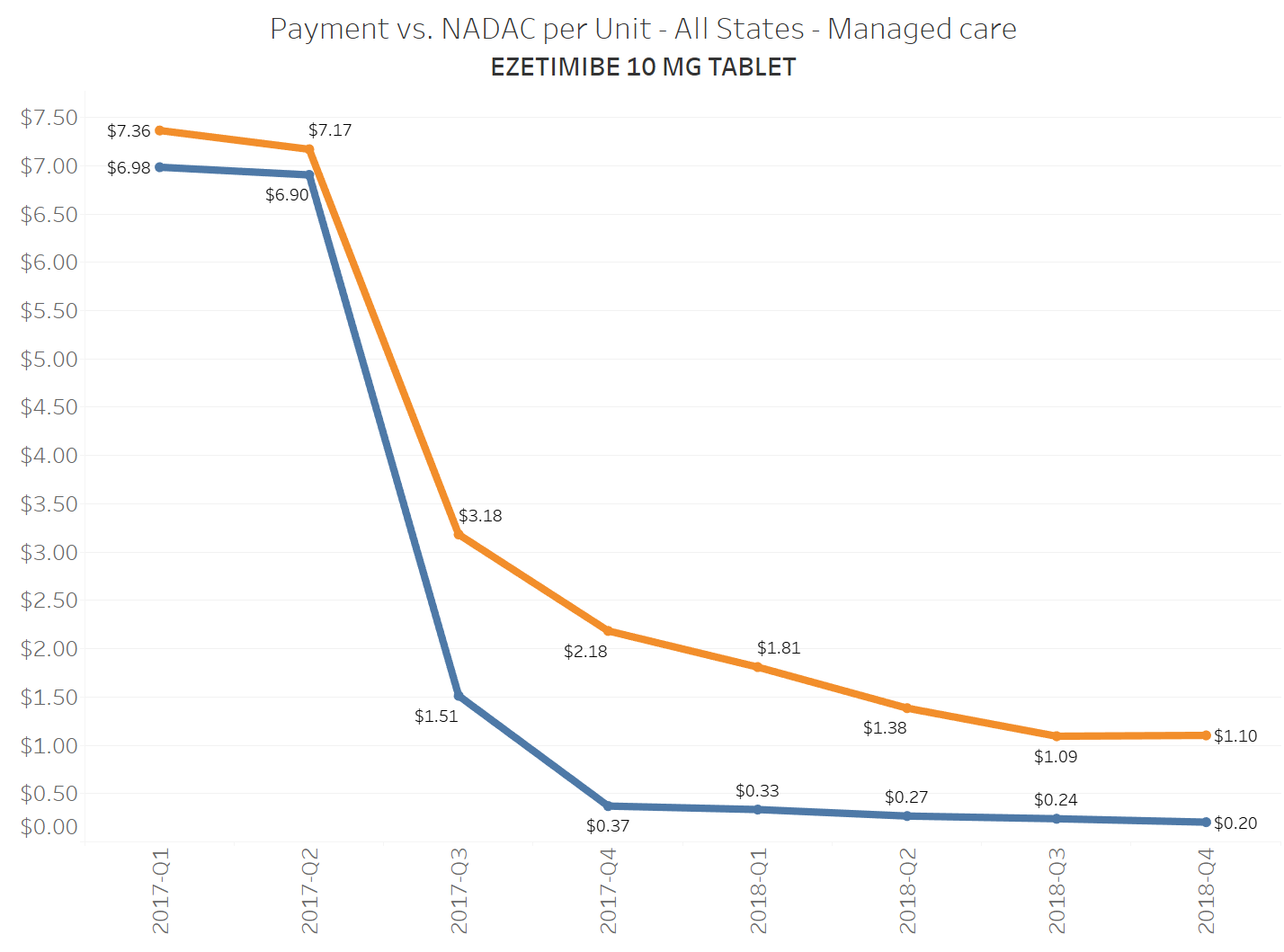

When a brand-drug goes off patent and its generic “copy-cat” comes to market, the first generic manufacturer usually gets 180-days of exclusivity as a reward for being first to file a drug application. As you would expect, when there is only one generic manufacturer, we don’t get significant savings. But when the 180-day period is over, multiple generic manufacturers come to market and drive the cost of the generic down to pennies on the dollar. This is typically referred to as when a drug goes “multi-source” You can see the multi-source impact on drug prices in the charts below (from our Drug Pricing Dashboard) with generic Benicar (Olmesartan Medoxomil), generic Effient (Prasugrel), generic Seroquel (Quetiapine ER), generic Viread (Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate), and generic Zetia (Ezetimibe). Once multiple manufacturers enter the market, the price of each drug craters.

But there is not always a 180-day exclusivity period. Sometimes, the generic is launched with three or more manufacturers in what is called a break-open generic. These generics can immediately produce massive savings upon release.

This is exactly what happened last week with Lyrica. On July 19, the FDA approved multiple applications for the first generics of Lyrica (pregabalin). Let’s be more precise. The FDA approved 10 applications. TEN! Now, 46brooklyn has only been around for less than a year at this point … but in that time, we’ve never seen an instance of a blockbuster generic drug coming to market with ten labelers.

Considering all the heat that Pfizer took for its pricing of Lyrica in the past, this break-open generic Lyrica (Pregabalin) launch is a big deal. Hell, there were people ready to throw patent-burning parties over this moment.

So the next logical question is, if you bring a generic drug to market with ten competing manufacturers, what will happen to the price?

Research has shown that more competition yields lower prices, and specifically, drugs experience significant deflation with only 4-5 manufacturers. What happens when 10 come to market at the same time?

We can answer this question, starting today. That’s because today is the first day that pharmacies can buy generic Lyrica (Pregabalin) from their wholesalers. Unfortunately that means this drug’s pricing won’t make it into the NADAC database for at least a couple weeks, so NADAC was not available for us to use quite yet. But pharmacists know the price of generic Lyrica, and we just happen to know a few pharmacists. So we called in some help.

We called around and asked several pharmacies for the invoice pricing (pre-rebate) offered by the top three drug wholesalers (McKesson, Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen) for generic Lyrica (150 mg – the most commonly dispensed strength). The pharmacies we talked to today reported that they can buy one of the ten generic copycats for somewhere between $15 and $20 per 90-count bottle. That’s $0.17 to $0.22 cents per capsule, or a 97% to 98% discount to brand-name Lyrica ($7.50 per capsule).

As FiercePharma’s Eric Sagonowsky pointed out this week, “FDA numbers show generic prices run about one-quarter the brand when 10 copycat drugmakers are fighting for share.” Well, in Lyrica’s case it’s considerably more than that.

To see almost all of the value sucked out of Lyrica essentially overnight is frankly incredible. This is an unbelievable amount of deflation to see on day 1 in the life of a generic, and shows how hyper-competitive the generic manufacturer market can be when it’s working properly.

How much savings could this generate?

We caveat this section by first saying that to truly answer the question of how much savings all this generic Lyrica deflation could generate, you need to know all the rebates being collected by health plans and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) on brand-name Lyrica today. As has been well chronicled, those rebates are notoriously secretive, so for the purposes of this exercise, we can only estimate the list price savings.

That said, in 2018, state Medicaid managed care plans bought $371 million of Lyrica (all strengths). If we could snap our fingers and all of the Pregabalin dispensed could be transferred over to the generic price (and it was reimbursed in a model that pays pharmacies at NADAC plus a ~$10 professional dispensing fee per claim), the same number of units would cost a measly $18.5 million.

Now, let’s scale up to Medicare Part D, which spent $2.5 billion on Lyrica in 2017 (the most recent data we have). If you switch all of that over to the generic price, it would have cost $126 million – that’s $2.4 billion in savings on one drug!

Figure 1

Source: Data.Medicaid.gov, CMS.gov, 46brooklyn Research

The actual savings we should expect our broken supply chain to deliver

But those are just the hypothetical savings that we would see if we had a drug supply chain that actually was designed to save payers money. As we have written extensively, that’s not what we have. Instead, we have a supply chain that charges payers for generic drugs based on a discount to their Average Wholesale Price (AWP), which is a meaningless benchmark for approximating true generic drug costs.

If we want to truly assess potential savings within the confines of how folks really pay for generic drugs today, we really need to know AWP; not the market-based acquisition cost. With that in mind, it turns out the median AWP across the ten labelers is $722 for a 90-count, or just north of $8 per capsule.

That’s right - a drug with a sticker price of $8 per capsule can currently be purchased by pharmacies (on day 1) for around $0.20 per capsule.

So, if you are a payer stuck in an AWP-linked PBM generic guarantee contract, eight dollars per Pregabalin capsule is the number that should matter most to you, because that’s the “made-up” sticker price your PBM is discounting off of. To be clear, you will almost certainly get some discount to the $8 sticker price (if not, you are in a rip-off contract of epic proportions) … but there is simply no guarantee that you will pay anything close to “cost-plus” for this generic.

To illustrate this dynamic, let’s go back to the five generics shown earlier in this report that experienced a large, nearly overnight collapse in pricing after going multi-source. We’ve added the weighted average Medicaid managed care cost per unit to these charts (take a look at our Medicaid Drug Pricing Heat Map to see these charts by state). The blue line represents NADAC as a proxy for the actual cost of the drug, and the orange line is what state Medicaid programs are being charged by their managed care plans and PBMs for the drug. To be sure, Medicaid managed care saved money on these generics, but not nearly enough when viewed in context with the drop in their actual acquisition cost.

A very timely case study

With more and more attention being drawn to PBM drug pricing tactics such as spread pricing, DIR fees, and massive Part D generic price variation, Lyrica offers a wonderful case study on the benefits that can be realized if more federal, state, and commercial generic drug spending was shifted over to an acquisition cost based model. If Medicaid managed care and Medicare Part D plans required cost-plus pricing models (similar to Medicaid fee-for-service programs) for generic drugs, more than $2.7 billion (less rebates, of course) would be erased from spending on this one drug.

But instead, payers in Medicaid managed care, Part D, and commercial pay for generics based on complicated formulas that rely on an inflated, meaningless, and more importantly, non-market-based generic pricing benchmark called AWP. So, instead of immediately realizing the significant benefits of generic competition, payers have to wait until their PBM contract is up to renegotiate a larger discount to the same meaningless aggregate AWP that better accounts for generic Lyrica’s actual bombed-out cost. But then of course, the next “generic Lyrica” will come to market and the payer’s problem starts all over again. Have fun on that hamster wheel.

Why do payers willingly enter into contracts that replace the pricing set by the hyper-competitive generic marketplace with pricing set by the highly-concentrated PBM market? It’s like paying Fidelity $25 to buy a stock that’s trading at $5. It simply makes no sense, until you recognize that this system is so intentionally complex, and the information is so well-hidden, that it is near-impossible for a payer to understand this well enough to demand a different approach.

We hope that this Lyrica example sheds some more light on the problem. Hopefully, managed care organizations, Part D plans, and self-funded employers will keep an eye on how much they are being charged for generic Lyrica, and will start to ask questions if it’s ever north of $0.40 per capsule. Or maybe rather than watching their PBM’s generic pricing like a hawk, maybe they’ll realize it’s just easier to anchor payments to a real market-based price.

The good news is that literally as we’re writing this report, we got our first major sign that the largest payer in this country (the federal government) gets this. In the Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act of 2019 (released for markup today), the U.S. Senate Finance Committee proposed that all of Medicaid “require payment for pharmacy management services to be limited to ingredient cost and a professional dispensing fee.” In addition, the committee proposed two dramatic improvements to the NADAC survey – first, making the survey mandatory; and second, beginning to collect information on off-invoice discounts that pharmacies receive from wholesalers. What a novel concept! Figure out what the drug really costs, and pay a reasonable dispensing fee on top of it.

Senate Finance has proposed a solution to the “Lyrica problem” illustrated in this report, at least within Medicaid managed care. It’s a great start. With NADAC getting better, it’s not a stretch to see this same requirement eventually cascade over into Medicare Part D and employers start to demand a “cost-plus” model within their plan design.