Wreck-fidera: How Medicare Part D has hidden the benefits of generic competition for a blockbuster Multiple Sclerosis treatment

Roughly two years ago, we put on our hardhats and went spelunking into the cavernous depths of the byzantine Medicare Part D plan cost share world to better understand and illustrate how the incentives created by the program’s design were bewilderingly injecting life into multi-source brands (i.e., “zombie brands”) and leading to warped, inflated pricing (and poor uptake) of their generic equivalents. We ventured down into these depths using Teva’s Copaxone as our case study, a blockbuster drug that treats certain types of multiple sclerosis (MS), and is no stranger to drama when it comes to pricing issues and patent games.

But the ironic story of how the federal government’s design of Part D (specifically its design of the coverage gap) backfired on Medicare and its seniors, protecting Copaxone from generic competition, simply had not been told. So, we wrote that story – complete with all the math that implicated the Part D program for its culpability in this scheme.

But there was one problem with our report. It was north of 7,500 words – every one needed in our view (ok, maybe not every word) to provide a full colonoscopy of how Part D’s complexity and poor incentives had aided and abetted drug pricing woes for our nation’s seniors. But, as we now fully realize, few people have the intestinal fortitude to fully digest 7,500+ words on the nuances of the Part D benefit design. So, nothing has changed … and now, two years later, history has repeated itself for the same Multiple Sclerosis (MS) community that had to bear the brunt of the Part D program’s structural failure with Copaxone.

Tecfidera, another blockbuster MS treatment – and Biogen’s highest revenue drug in 2019 – went generic in late-2020 after Mylan prevailed in their challenges against Biogen’s patents (the first time that is; they just prevailed again on 11/30). Within months of the favorable ruling for the generic manufacturers, more than ten generic drug makers brought competing versions of dimethyl fumarate to market with “deeply discounted prices to Tecfidera.” Mind you, those are not our words. Those are Biogen’s words, which they provided in their latest quarterly financial report. Biogen went on to state that, “generic competition for TECFIDERA has significantly reduced our TECFIDERA revenue and is expected to have a substantial negative impact on our TECFIDERA revenue for as long as there is generic competition.” And while Biogen may have launched Vumerity to mitigate this (which in our view is a prototypical example of a product hop, if for no other reason than the fact that Biogen’s Tecfidera.com literally “website hops” and re-directs to a pitch for Vumerity), this bad news for Biogen must be good news for patients and plan sponsors, correct?

Perhaps the better question is, would we be writing this report if it was that simple?

If generic prices are “deeply discounted,” those discounts should be making it back to the payer, and ultimately, the patient … right? As you likely have guessed by the sarcastic way we phrased this rhetorical question, they are not.

As you will see in this report, the savings are instead getting stuck in the cluttered, inefficient, junk-food-laden intestine that is the U.S. drug supply chain rather than cleanly and quickly passing out the other side to the patient.

But the story of Tecfidera is not simply part two of our Copaxone story, except this time with toilet metaphors. In our view, Tecfidera’s story is even more frustrating than Copaxone’s, because in Tecfidera’s case, the efficient, high-fiber generic marketplace actually worked very quickly and effectively, with aggressive competition piledriving prices down to where you can find a 60-count bottle of the generic equivalent today (roughly one year post generic launch) for a 99%+ discount to the brand’s list price.

That bears repeating: The generic’s market-competitive acquisition cost for generic Tecfidera is 99%+ off the brand’s list price as of November 2021.

So then why did we find that in Q3 2021, Medicare Part D plans covering the majority of U.S. seniors didn’t even make the generic equivalent available to their members; instead only offering them brand-name Tecfidera? And then when the generic was made available to seniors, it was largely done so at “negotiated prices” that far exceeded the lowest cost generic equivalent’s list price?

You read that right … as we will show in this report, Part D is collectively expending all of its “negotiating” effort on this blockbuster MS treatment to deliver far worse rates than it could get if it just purchased the lowest cost option directly from the generic manufacturer (with no rebates)!

Something doesn’t add up here. And spoiler alert … while we have some high-conviction theories on the subject, we don’t have all of the data we need to conclusively answer why plans are hiding the truth about generic Tecfidera pricing from their members and the federal government. But we do have the data to solidly illustrate Part D’s systemic failure, and while this wouldn’t meet Axios standards for brevity, we will not let this data get lost in a sea of words again.

So, in the spirit of continuous improvement, we’ve approached this report differently. Instead of writing yet another dissertation, we’ve tried to tell the story through a series of what we’ll call (for lack of a better term) “chapters.” Each chapter will include one to two graphics, and no more than two to three paragraphs of discussion to help explain the meaning of the graphics. Think of it as reading the prescription drug pricing equivalent of Where the Wild Things Are (except our big scary monsters are big, largely imaginary [in the sense that they’re simply made up], drug prices).

Overall, we’ve compiled nine of these chapters, after which we will wrap up with recommendations. Hopefully this format will be more palatable than our typical meandering style, and will spark much-needed debate about the changes Part D requires to better align incentives and to prevent Part D’s ugly history from repeating itself yet again.

Note that for the sake of simplicity, we will be using Tecfidera 240 mg (which is far more utilized than the 120 mg strength) and its’ generic equivalents for our analysis throughout the report.

Chapter 1: Tecfidera’s days of exclusivity

Figure 1

Source: 46brooklyn Research analysis of Elsevier Gold Standard Data

In 2019, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society estimated that Multiple Sclerosis (MS) affects between 337.9 and 362.6 of every 100,000 Americans, equating to 1.1 to 1.2 million American lives. MS is a neurological disease in which the body essentially attacks itself, leading to numbness, tingling, muscles spams, walking difficulties, and pain. The disease is the most progressive neurological disease among young adults worldwide. Management of symptoms is an essential part for maintaining a high quality of life. Initially, pharmacological options were limited to injections or infusions, posing barriers to treatment for some. But hope for mitigation of these barriers arrived on March 27, 2013, when Biogen received FDA approval for Tecfidera.

Tecfidera launched in 2013 with a list price (i.e., Wholesale Acquisition Cost, or “WAC”) for a one-month supply of ~$4,500. That’s 60 capsules per month at around $75 per dose. This initial list price equated to an annual cost to treat (to be shared by patient and health plan, before the health plan receives any rebates) of $54,000. With the combination of the price and the drug’s expected value at launch, Tecfidera was predicted to be a “big hit.” And it was. As patient uptake grew, over the next eight years, Biogen implemented 10 price increases, bringing the current list price for a one-month supply to $8,276, or $138 per unit (Figure 1). This equates to a total annual treatment cost (again, before any rebates paid to the pharmacy benefit manager / health plan) of $99,300 – an increase of 84% from the drug’s launch.

Chapter 2: Mylan’s patent challenge prevails, and generics flood the market

Figure 2

Source: 46brooklyn Research analysis of Elsevier Gold Standard Data

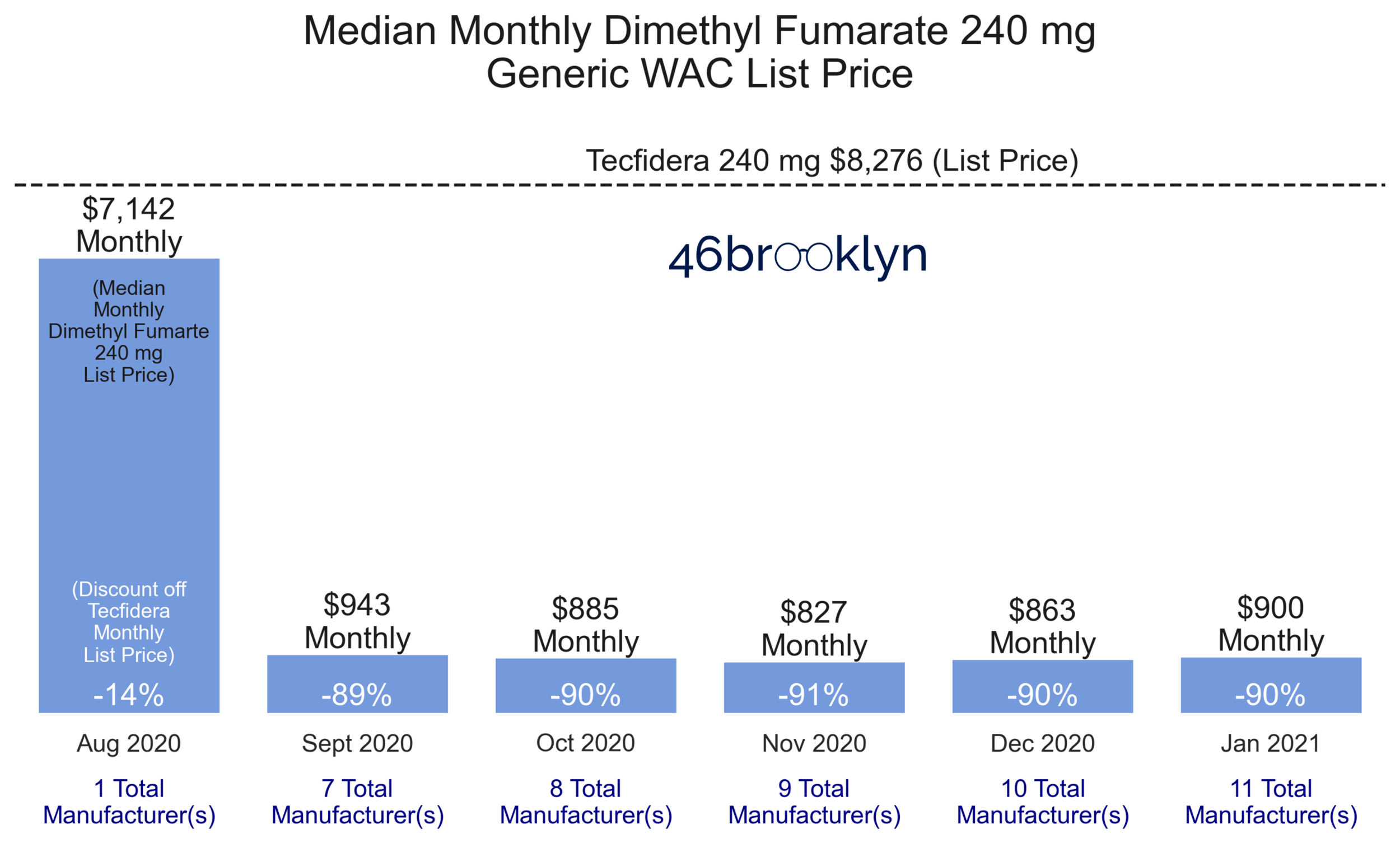

In 2020, Mylan Pharmaceutical challenged Tecfidera’s ‘514’ patent in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Initially, Biogen successfully defended its intellectual property and maintained proprietary rights. However, not to be deterred, Mylan filed an additional suit in its home state of West Virginia. This new challenge also took aim at the ‘514’ patent but argued the patent should be voided due to Lack of Written Description. On June 18, 2020, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of West Virginia sided with Mylan. The court concluded that on the effective date of the patent (February 8, 2007), Biogen did not have in its possession the intellectual property needed to make claims pertaining to the specific dosing regimens to treat multiple sclerosis. Just two short months later (August 19, 2020), Mylan launched the first generic version of Tecfidera 240 mg (dimethyl fumarate) with a Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) list price set at a 14% discount to Tecfidera.

After Mylan’s entry, the proverbial floodgates opened, with six more generic drugmakers coming to market with competing versions of dimethyl fumarate by the end of the following month. In just one month, the median WAC list price of dimethyl fumarate 240 mg eroded by 89% (relative to brand-name Tecfidera) to $943 for a one-month supply (Figure 2). Of note, by the end of January 2021, there were 11 different manufacturers competing for the generic dimethyl fumarate market, with the lowest cost version carrying a WAC list price of just $350 for a one-month supply – a jaw-dropping 96% discount to brand-name Tecfidera.

Chapter 3: The generic market succeeded in driving down the cost of dimethyl fumarate

Figure 3

Source: 46brooklyn Research analysis of data from Elsevier Gold Standard Database, Data.Medicaid.gov, and Blueberry Pharmacy

Rolling the tape forward to the end of October 2021, generic Tecfidera now is a much more affordable drug for pharmacies to purchase. While its median WAC ($900 per one-month supply) and lowest cost WAC ($350 per one-month supply) have not changed much since the start of the year, its National Average Drug Acquisition Cost, or NADAC (i.e., the invoice cost at which retail pharmacies acquire a drug from their wholesalers), is now $184 per one-month supply. To be clear, the NADAC tells us that the average community pharmacy can buy generic dimethyl fumarate at a 97% discount to brand-name Tecfidera, before any rebates they may receive from their wholesaler.

But that’s an average pharmacy, buying this drug from an average wholesaler. What about a pharmacy that aggressively shops with smaller (i.e., secondary) wholesalers to get the absolute best available net acquisition cost on this drug? Our friends at Blueberry Pharmacy (a small, independent ‘cash’ pharmacy outside of Pittsburgh, whom we profiled earlier this year in our Truvada report) have done exactly that, jettisoning both the traditional insurance and wholesaler models to aggressively drive down costs on generic drugs for their patients.

This is an interesting scenario for us to explore. It’s effectively asking the question, what would generic Tecfidera’s price be if we stripped all of needless complexity out of the U.S. drug supply chain and just let pharmacies buy drugs from the cheapest wholesale option? That would be great for pharmacies, but in return, we would also need pharmacies to transparently pass their acquisition cost through to their patients, plus a fair and transparent markup for their overhead and service. The answer is that, in this scenario, we get an all-in, out-the-door cost of (drum roll please…) just $40.32 per month supply for generic Tecfidera (Figures 3 and 4)!

That’s a 99.5% discount to brand-name Tecfidera’s price. And this is a real price you can get today – a price that even includes the pharmacies’ margin associated with monitoring the patient's blood work (which arguably is all that really makes dimethyl fumarate a “specialty drug”; at least as special as a drug like warfarin [note: few consider warfarin special]).

Figure 4

Source: Blueberry Pharmacy

Chapter 4: Investigating the alternate Part D universe where more than half of all seniors don’t even know generic Tecfidera exists

Figure 5

Source: 46brooklyn Research analysis of Q3 2021 Medicare Part D formulary and coverage files

So, we now know that generic Tecfidera’s true cost is super-cheap for pharmacies – the competitive generic marketplace did its job beating down the pharmacy acquisition cost to pennies on the dollar (vs. brand-name Tecfidera), saving Americans living with MS gobs of money in the process. Right?

Wrong.

When we checked the latest Q3 2021 Medicare Part D formulary and pricing data (now available through a free download from CMS.gov), we found that Part D plan sponsors responsible for over half the patient lives in Part D with Tecfidera coverage didn’t even make generic Tecfidera available! This is because the formulary files, or the list of drugs covered by their Part D plan – which as we said are now graciously publicly available – show that they are not.

The lightest blue bar in Figure 5 shows that as of Q3 2021, there were 24,053,426 million seniors (52.3% of Part D lives) that were on plans that mandated brand-name Tecfidera. In other words, for over half of Part D seniors, all the intense generic competition that has driven the lowest generic acquisition cost we could find to a >99% discount to the brand was a moot point – thanks to their health plans and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), these folks sadly still live in a very expensive brand-only world.

Meanwhile, only 3.82 million seniors (8.3% of lives in Part D) are covered by Part D plans that recognize the affordability of generic Tecfidera viz-a-viz brand-name Tecfidera, and have gone so far as to mandate the more affordable option.

What gives here?

Chapter 5: This alternate universe is largely being created by the largest Part D plan sponsors

Figure 6

Source: 46brooklyn Research analysis of Q3 2021 Medicare Part D formulary and coverage files

It looks like the answer to this question starts with questioning the largest Part D plan sponsors. Figure 6 clearly highlights that the largest plans are overwhelmingly sticking with Biogen’s brand-name Tecfidera rather than switching to a generic equivalent. Note that seven large parent organizations (CVS, UnitedHealthcare, Cigna, Anthem, Kaiser Permanente, Humana, and Centene) are responsible for providing Part D coverage to over 85% of seniors in Part D that have Tecfidera coverage (Figure 7). This paints a vastly different picture on how much competition there truly is within Medicare Part D (and raises some eyebrows on how much good consolidation is really doing for Part D).

Figure 7

Source: 46brooklyn Research analysis of Q3 2021 Medicare Part D formulary and coverage files

With this as context, now take a peek once again at Figure 6, in which we split out brand mandate, choice (i.e., you have the option to get the brand or the generic), and generic mandate for Tecfidera. Nearly all the lives that are being subjected to a brand Tecfidera mandate are being managed by one of these seven large parent companies. How do we reconcile this finding?

Are we really to believe that some of the largest health insurers on the planet (which, by the way, nearly all own specialty pharmacies) never got the memo that Tecfidera not only has a generic equivalent, but can be acquired by a small pharmacy for 99% off the brand’s price? No, that would be absurd.

A more likely explanation is that between plan design, rebates (aka money from sick people), and risk corridor payments, these plans make more money by covering the brand over its cheaper generic.

We explored some of how this works very recently with insulin, where plan/PBM rebate-chasing foists higher out-of-pocket costs onto patients. Whatever the reason, the fact remains that many large plans and their PBMs are explicitly blocking generic Tecfidera uptake in Part D.

However, not all large plans are equally responsible for injecting life into this zombie brand. As shown in Figure 8, only four of the seven organizations (Humana, CVS, Centene, and Anthem) have brand mandates, while the other three at least have the decency to make the generic available as an option. Humana has a single contract of 9,101 lives that mandates generic utilization. Unfortunately, the additional 8.2 million lives managed by Humana do not have a generic option.

Figure 8

Source: 46brooklyn Research analysis of Q3 2021 Medicare Part D formulary and coverage files

Chapter 6: Forget what you learned in Econ 101; the traditional impact of economies of scale don’t apply to buying drugs

Figure 9

Source: 46brooklyn Research analysis of Q3 2021 Medicare Part D formulary and coverage files

We know this goes against what most of us were taught in grade school, so we’ll say it as simply as we can and then let the violin chart in Figure 9 speak for itself – bigger size equals higher costs when it comes to prescription drugs. The above chart shows the cheapest negotiated price for any version of dimethyl fumarate (brand or generic) that each Part D plan (by plan size grouping) had listed within CMS’ Q3 2021 pricing data. Note that the fatter the blob on the violin chart, the more patient lives had access to this drug at the corresponding price (i.e., the larger the size of the Part D program). As an example, check out how fat the blob is for large plans above Tecfidera’s list price. This indicates that large plans are subjecting a whole lot of seniors to point-of-sale “negotiated prices” that are even higher than Tecfidera’s list price!

But note as we move from right to left on the chart, the blobs at the higher negotiated price points get narrower, and the blobs at the lower negotiated price points get fatter. In fact, some of the lowest negotiated prices available in Part D for generic Tecfidera are being reported by some of the smallest plans. That’s the exact opposite dynamic we were taught in our economics classes, and likely also surprising to the government powers-that-be that signed off on so much health plan integration/consolidation in the hopes of driving down costs for Americans.

As you let this chart and its counterintuitive findings sink in, make sure to take note of the bottom dashed line. We’ve already mentioned the significance of the $350 mark to this study. $350 represents the lowest WAC list price set directly by a generic manufacturer. Consider that Part D plans are supposed to be “negotiating” discounts to list prices to help save seniors money. They are able to do this because we’ve banned the federal government, i.e., CMS, from doing it on their behalf (unlike other countries across the globe).

Clearly, Part D plans are failing miserably in this respect – we found that only 0.22% of all lives in Part D had access to dimethyl fumarate at a negotiated price below $350 per month supply in Q3 2021. We don’t blame you for wondering what purpose there is in letting plans negotiate pricing if it results in a far higher price than is directly available from the manufacturer. And we’re talking far higher.

Say a plan negotiated a price of $2,000 per month for generic dimethyl fumarate, which relative to the average Part D plan, is (sadly) a very good price. Even at that “very good” price, that’s like hiring an expert middleman to negotiate a purchase of a Toyota Camry (MSRP = $25,295) for you and getting a bill for $144,542 ($2,000 / $350 x $25,295). Who would do that? #ushealthcare would.

This math and logic is completely nonsensical when applied to anything outside health care.

Chapter 7: Even when the generic is available, it’s still considered a specialty drug

Figure 10

Source: 46brooklyn Research analysis of Q3 2021 Medicare Part D formulary and coverage files

But the story is not all bad, right? If you are glass-half-full type of person (with exceptionally low standards), you could turn our analysis upside down and celebrate the fact that nearly half of seniors with Tecfidera coverage in Part D actually can access Tecfidera’s cheaper generic equivalent. 🎉

Well, sorry to drain your half-full glass, but when we dug deeper into the plans that made the generic available, we found that almost all placed it on Tier 5, which is the tier purportedly reserved for specialty drugs. This tier also typically subjects patients to coinsurance (not copay) of a minimum 25% charge … and remember – that’s 25% of the negotiated price, which as we learned in the prior chapter, is typically VASTLY higher than the most competitive generic manufacturer’s list price.

Despite all the drug pricing monsters we’ve found in this scary jungle of Part D plans, we do have to give respect where it’s due (once again) to Kaiser Permanente, who by and large is responsible for the entirety of the 1,722,407 lives managed by “Large” plans that have placed generic dimethyl fumarate on Tier 2. As we found in Copaxone, Kaiser is quite good about placing generics where they belong (the lower Tiers), which saves patients big money out of pocket since Tier 2 copays are generally around $10-20 per claim. So, once again, kudos to Kaiser for managing Part D drug benefits for Tecfidera in line with the spirit of the program. Sadly, you are once again the exception to the rule.

Beyond this one Kaiser bright spot, Figure 10 paints a pretty bleak picture. How can a highly competitive generic drug with such a low acquisition cost be predominantly considered to be a specialty drug, irrespective of the size of the plan?

Chapter 8: Part D negotiated prices for dimethyl fumarate are completely out of whack with reality

Figure 11

Source: 46brooklyn Research analysis of Q3 2021 Medicare Part D formulary and coverage files

Not to beat a dead horse, but as should be clear by now, the answer is that the vast majority of Part D plans that offer Tecfidera coverage aren’t reporting negotiated prices that are in the ballpark of the actual acquisition cost for dimethyl fumarate.

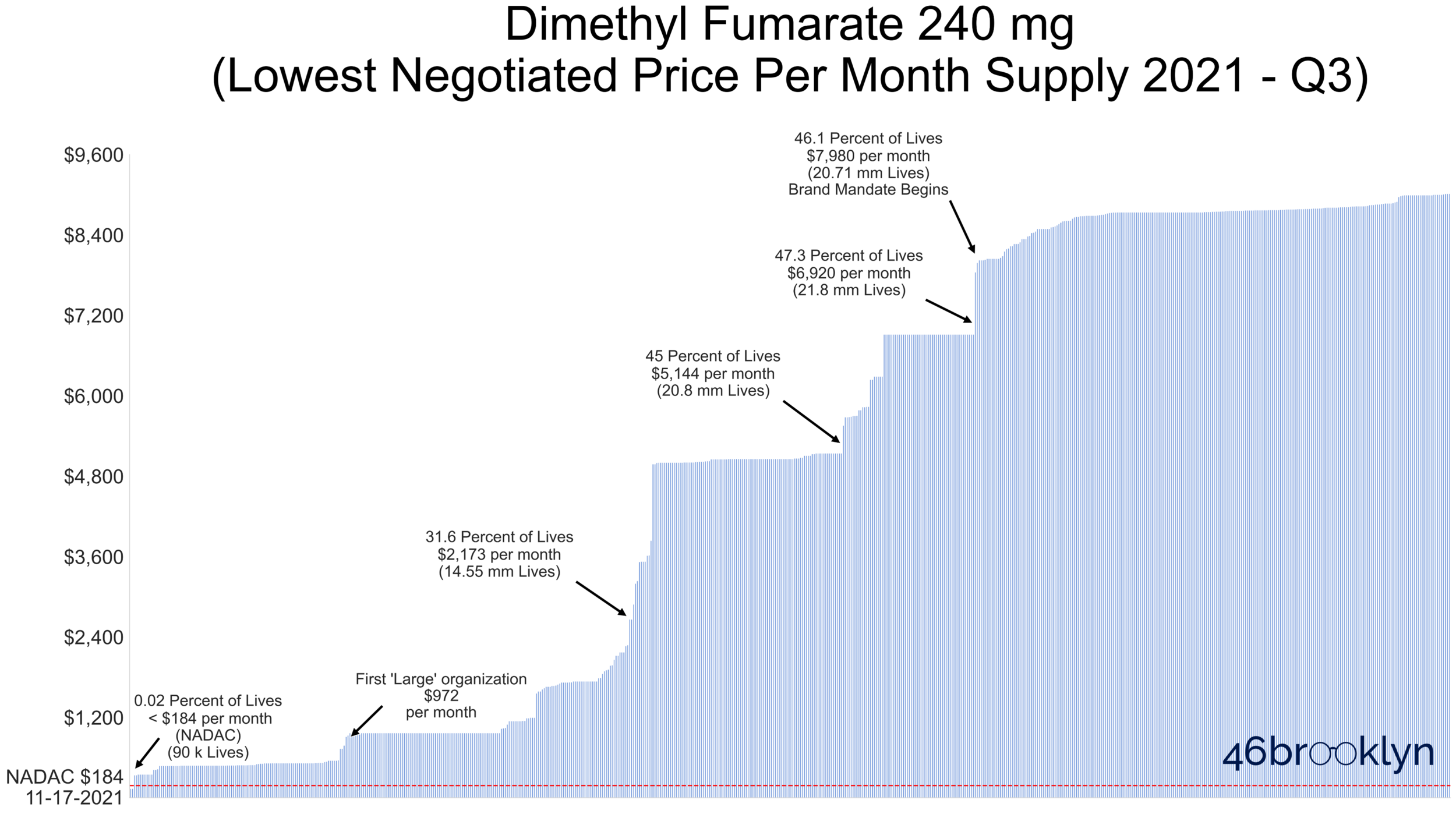

Figure 11 displays a vertical line for each Part D contract ID – all told, there are nearly 600 different contract IDs that reported a negotiated price for dimethyl fumarate (brand or generic) in Q3 2021. We simply took the lowest cost option for each contract ID and rank ordered all the contracts from lowest to highest price (from left-to-right).

Note that the x-axis is showing you cumulative lives covered in Part D – we added annotations to the chart to help you get your bearings on how many seniors have access to dimethyl fumarate at different negotiated price points. For example, the third annotation tells us that 31.6% of lives have access to dimethyl fumarate at a negotiated price per month supply of $2,173 or less. This means that roughly 70% of seniors are being subjected to negotiated prices at the point of sale of more than $2,173 per month. For reference, the red dotted line at the far bottom of the chart shows the average pharmacy acquisition cost of this drug, which is $285 for a month supply. Less than 0.02% of all seniors have access to dimethyl fumarate at a negotiated price below NADAC. Being math geeks, we’re going to go ahead and round that down to 0%, which means (mathematically-speaking) no one has access to generic Tecfidera at pharmacy cost in Medicare.

With negotiated prices as high as shown in Figure 11, it’s no wonder Part D plans consider dimethyl fumarate to be a specialty drug, especially given that CMS defines a specialty drug as one that costs $670 per 30-day supply).

The problem here is that CMS appears to have little clue what generic Tecfidera actually costs, and no regulatory authority to crack down on abusive (or incompetent?) “negotiation” of prices.

Returning to our car analogy, this entire travesty is like your expert middleman negotiator explaining to you that the Toyota Camry for which you paid more than $140,000 is really a Maserati. Yes, it may look exactly like a Toyota Camry, and have all of the components of a Toyota Camry, and come from a Toyota factory, and say “Toyota Camry” on the invoice in your hand … but forget all that – it’s a Maserati. Confused, you turn to CMS and look for an explanation, to which it shrugs its shoulders and responds, “we dunno … guess it’s a Maserati.”

Chapter 9: MS patients could save $5,800+ per year if Part D delivered truly competitive costs for dimethyl fumarate

Figure 12

Source: 46brooklyn Research analysis of Q3 2021 Medicare Part D formulary and coverage files

In our view, the key takeaway from our analysis is how much this currently-designed “negotiation” process is costing Part D members living with MS. Recall that over half of all Part D members are being forced into using the brand, and as such are being subjected to Tecfidera’s elevated WAC list price at the point-of-sale. If we model out the cost share for these patients, we estimate that each will end up shelling out roughly $7,200 for Tecfidera each year. To put some context to this number, $7,200 works out to be 14% of median household income or 24% of median individual income. And that’s just for one therapy (of many) to keep their symptoms at bay.

Now what if these patients instead had the option to participate in a program that skipped the entire current “negotiation” process and simply bought the lowest WAC list price alternative for its members? This is no different than going to the grocery store to buy acetaminophen and just choosing the cheapest option on the shelf. Remember, right now generic dimethyl fumarate is available from a drug manufacturer for $350 per month supply. Theoretically, Part D could have just bought a boat-load of dimethyl fumarate from this one manufacturer and provided that to all of its members. Going forward, if Part D removed the plan intermediaries from the equation and just bought the cheapest dimethyl fumarate option on “the shelf,” MS patients taking dimethyl fumarate would each save $5,816 per year.

All told, the horrible incentive alignment and lack of transparency within drug pricing in the U.S. has resulted in negotiated prices far eclipsing list prices. This program failure has produced out-of-pocket costs for dimethyl fumarate for patients that are 5.2x higher than they would be completely absent any negotiation.

Unearthing and restoring the hidden hardwood floors

Given how much we love analogies, we’ll close with one for the DIY home repair crowd – a highly relevant theme, considering current federal efforts to “Build Back Better.” For those readers that have ever purchased and renovated an old home, or even those that have ever watched just about any show on HGTV, you know well that in an old home, there’s a good chance that under multiple layers of linoleum floors, may lie beautiful, original hardwood floors. Once discovered, you’ll have to roll up your sleeves and pull up the ratty, smelly, stained, asbestos-laden floor coverings to get to the original hardwood floors, which isn’t easy. But once those floors are restored, it completely changes the look and feel of the room, injecting it with character and elegance matching the original intent of the home.

Despite our Medicare Part D “house” only being 15 years old, linoleum floors have piled up quickly as the both the program and the U.S. drug supply chain have exploded in complexity. Now here we are, with yet another case study that should make all seniors cringe. Here we have a blockbuster drug that goes generic, and as we have shown, it proceeds to crater in price (just like generic drugs typically do). But seniors are missing a mechanism to ensure that these savings directly flow over into Part D.

Instead, CMS has fully outsourced the responsibility of “negotiating” fair, market-competitive prices to Part D plan sponsors, who thanks to the mash-up of clandestine rebates, complex risk corridor payments, conflicts of interest, and the warped Part D benefit design (i.e., who pays for what in different coverage phases), largely have the economic incentive to hide the true market price of a drug. In other words, seniors are left to stand on layers upon layers of ugly, unhealthy linoleum flooring with no way to know what hidden treasure lies underneath. And they’re stuck. Without intervention from CMS or Congress, it’s foolish to expect that most plans are coming to help them, because they simply don’t have the incentive to do so.

Recommendations

We don’t normally provide direct recommendations in our reports, but at the risk of stepping outside our lane as researchers, in this case we will, as we really don’t want to write this same report another two years from now. Said differently, we’re tired of ripping up these floors and want to build back better. That said, outside of a needed overhaul of the pricing and system design, here are some more measured recommendations that could be considered to rectify this problem based upon what the data is telling us.

Fix the Medicare Part D cost share

In our view, much of the problems with Part D start with the its complex plan design. As we showed in our Copaxone report, the design of the coverage gap provides a cost advantage to brand drugs viz-a-viz their generic equivalents. This is because manufacturers are asked to pay a meaningful portion of brand-drug costs in the gap, with all of these dollars counting towards the patient’s TrOOP (true out-of-pocket) threshold. This acts as an accelerator of sorts for brand drugs, speeding patients through the coverage gap and into catastrophic, where they (the Part D plans) are only responsible for 5% of the drug’s negotiated price. This mechanism doesn’t exist for generics, meaning that seniors spend more time and money in the coverage gap if they choose a generic. This gives the brand an unfair advantage over its generic equivalents, potentially limiting generic uptake while also costing the government (i.e., us as taxpayers) a good deal of money.

The other problem we see is that plans simply aren’t responsible for paying much of their elevated negotiated prices in the catastrophic coverage phase – they only pay 15% of the bill after their patient blows through their TrOOP, but collect all the rebates on the back end for this spending (and due to the complexities of the risk corridor design, get to keep a disproportionate share of those rebates). Again, we recently explored this incentive with insulin in typical commercial markets. So it makes sense that plans would prefer to choose high cost, high rebate drugs – that’s generally how they make more money! This also explains why plans are now overwhelmingly overpaying pharmacies at the point-of-sale, and then taking back this money (and more) after the fact in the form of “DIR fees.” Again, higher point-of-sale costs don’t matter much to plans, as the cost share protects them from those costs. There’s more value in collecting the money after the fact.

The good news is that a plan design fix may already be in the works. If you made it to page 2,064 of the latest iteration of the Build Back Better Act, you’ll stumble across a section called “Medicare Part D Benefit Redesign.” While we are in no way experts in reading legislative text, our interpretation of this rule is that it would rid Part D of the coverage gap, cap seniors out-of-pocket expenses per year at $2,000, and shift more of the burden of high drug costs in catastrophic onto the plans and drugmakers. In our view – while we admittedly don’t have a complete understanding of the total policy ramifications – these changes would seem go a long way to fixing the underlying warped incentives responsible for the findings in this report.

Require that generics are automatically added to all formularies when a generic goes multi-source

Currently, CMS has a very hands off approach to formulary management in Part D. If large plans want to mandate a brand medication over a generic alternative that’s 90%+ cheaper, CMS is effectively saying, “do whatever floats your boat, plan sponsor – all of the competition in Part D will sort itself out.”

If we have learned anything from this work, it’s that Part D is structured in such a way where competition cannot be relied upon to efficiently deliver the lowest cost alternatives to seniors for their drugs. An example of this, beyond just the pricing distortions we’ve focused on, is the consolidation of most of Medicare’s lives into a few large plans who don’t appear to be using their economies of scale as Econ 101 taught us they would. In fact, as witnessed with Tecfidera, effective competition may do the exact opposite.

Fixing the cost share will help align plan sponsor incentives with those of their members, which should help with generic uptake across Part D. But that’s still an indirect fix to this problem. An additional fix CMS could implement is to require all plans to make the generic available as soon as it goes multi-source. By multi-source, we mean where there are at least two competing generic manufacturers, which is really when generic price declines start to kick in.

Mandate that generic pricing is market competitive

With 99.8% of seniors on Part D plans that are delivering a negotiated price for dimethyl fumarate that’s more than the lowest cost generic manufacturer WAC list price, the struggles of the Part D program to deliver responsive, market-competitive prices on generic drugs appears to be systemic. Without getting too deep in the weeds, the reason why this problem is systemic is that CMS allows its plan sponsors to sign contracts with PBMs that price drugs off of Average Wholesale Price (AWP), which as we have written extensively, is the furthest thing from market-competitive drug pricing that exists in this country. Plans sign contracts with PBMs (the two are often the same company now) based on these discounts to totally bonkers AWP pricing, and then claw back DIR from pharmacies after the fact – DIR that has grown by 91,500% since 2010.

In essence, plans have abused CMS’ flexibility in how they contract with (largely their own affiliated) PBMs to set high negotiated rates on the front end – again, for which they are not really responsible due to the cost share – and keep more of the money flowing back to them through DIR pharmacy “rebates.” If this scheme sounds familiar to our Ohio audience, it should, because the state Medicaid director Maureen Corcoran lamented similar phony, inflated prices from PBMs in a recent hearing on “effective rate clawbacks” within their managed care system. Different program, same shell games.

CMS could quickly eliminate this problem by requiring plan sponsors to use an invoice-based reimbursement methodology as a condition of their participation in the Part D program. The most notable, publicly-available, invoice-based pricing benchmark is the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC), which today is the ingredient cost benchmark for many state-run Medicaid programs. However, many states conduct their own Actual Acquisition Cost (AAC) surveys, which CMS could rely on in some manner as well. Ultimately, we are agnostic on how CMS determines drug acquisition cost, so long that they require plans to contract based on some trusted measure of actual pharmacy acquisition costs, rather than relying on the non-existent altruism of the drug supply chain participants.

Require that generics are on lower tiers than equivalent brands

It feels strange even having to write about the logic in requiring cheaper generic equivalents to be on lower tiers than equivalent brands. If Part D is ultimately meant to serve seniors (is that still the point?), and there are cheaper generic equivalents available, why not require plans to pass on these savings to seniors through lower copays/coinsurance? From the patient’s perspective, this could be the most important change of all. Imagine if, like Kaiser Permanente, all plans had generic dimethyl fumarate on Tier 2. Patients would be paying $15 per fill. Plans could still create headaches for pharmacies and CMS’ accountants by paying overinflated negotiated rates at the point of sale and taking back this money after the fact through DIR, but at least the patient is no longer directly caught up in this madness.

We’d be remiss if we also didn’t mention that CMS also needs to monitor its plan sponsors to make sure that they are not stashing inexpensive generics on higher tiers. Generic acquisition costs decline rapidly as more competition comes to market, especially early in the generic’s life. When this happens, seniors need to trust that they will benefit from such deflation in the form of lower copays and/or coinsurance. This may be a redundant recommendation if CMS shifts to mandating market-competitive pricing, but if generic pricing remains anchored to fundamentally broken AWPs, as it is today, there will need to be some monitoring/regulatory mechanism to make sure that plan sponsors are not overcharging their members through such tier manipulation.

Fix Plan Finder to truly optimize drug costs for seniors

We’ve expressed our frustrations with Plan Finder before, but it’s time to revisit them again. Plan Finder is simply not designed for seniors to find the right plan AND right pharmacy to deliver the lowest cost on their drugs. Instead it is designed to only display the lowest cost plan AFTER the user has selected his/her pharmacy. With extreme pricing variability from one pharmacy to the next (note that this is driven by the plan/PBM, as pharmacies are largely price-takers; not price-setters), this design flaw dramatically reduces the effectiveness of Plan Finder.

Let’s go back to our the Kaiser Permanente example we wrote about a year ago. If you live in Kaiser’s service area, but are forced to choose your pharmacy before you get a list of plans, you will only see Kaiser come up as the low-cost option (again since they are placing “specialty” generics on Tier 2) if you first enter a Kaiser Permanente pharmacy. This is ridiculous! Kaiser runs a fully integrated model, so by definition, you only use a Kaiser pharmacy if you are already on a Kaiser plan. It’s a chicken and and egg situation that is preventing seniors from actually identifying the lowest cost option to procure their drugs.

This should be an easy fix for CMS (at least conceptually). Just present the user with an option to optimize both their plan and pharmacy, and make sure to tell them that doing so (i.e., being willing to switch pharmacies) could save them considerable money.

Investigate dispensation patterns and utilization of “specialty drugs” at specialty pharmacies affiliated with health plans

One of the shortcomings of CMS’ publicly-available formulary and pricing data is that it does not include utilization. To get utilization by pharmacy, one needs access to the Prescription Drug Event (PDE) data, which we unfortunately do not have. Somehow Medicare requires more secrecy than Medicaid, whose data is freely and publicly available – and able to be studied and utilized by all, including a few drug pricing nerds from Ohio. But without PDE data, we cannot perform an analysis to evaluate the potentially anti-competitive behavior that could come along with health plans owning their own PBMs and specialty pharmacies. The risk here is clear: the health plan could theoretically “negotiate” a price for a drug with itself (i.e., the PBM), and then pay that money out to itself (i.e., the pharmacy). Without the utilization data to analyze this, we cannot know the extent to which this is happening.

But where there is smoke, there is usually fire – and the “smoke” is clear for dimethyl fumarate. First, plan sponsors are “negotiating” far higher prices on dimethyl fumarate than we would expect from a a highly-competitive, efficient market. Second, 90% of plans are placing the generic on Tier 5, which pushes the patient to a specialty pharmacy, and away from the plan’s retail network. Third, all large health plans (except Anthem, who uses CVS Specialty Pharmacy) own their own specialty pharmacy (CVS Health = CVS Specialty Pharmacy; UnitedHealthcare = Briova; Cigna = Accredo; Humana = Humana Specialty Pharmacy; Centene = Acaria). Thanks to the spate of vertical integration in this space over the last decade or so, there is a lot of smoke here, and not a lot of transparency into whether or not these potential conflicts are being appropriately monitored and managed by CMS. As such, we believe further investigation is necessary to identify and size potential anti-competitive behavior.

“At some point, we can’t afford all of these “savings.””

The methodology for this report can be accessed here.

The research and analysis detailed in this report was performed by 3 Axis Advisors LLC (“3 Axis”) with support from Arnold Ventures. With permission from Arnold Ventures, the 3 Axis team donated all work product created during throughout this project to 46brooklyn Research, in recognition of the project’s alignment with 46brooklyn’s mission and research focus, and in hopes of the analysis and its takeaways reaching a broader audience. 3 Axis Advisors / 46brooklyn Research is grateful to Arnold Ventures for its support, and even more grateful for its shared desire to bring radical transparency to the very opaque U.S. pharmaceutical marketplace.